Black-billed magpie

In today's world, Black-billed magpie is an issue that has gained great relevance in society. With the advancement of technology and globalization, Black-billed magpie has become a question of interest to many people in different fields. Whether on a personal, professional, political or cultural level, Black-billed magpie has generated debates and discussions around the world. In this article, we will deeply explore the topic of Black-billed magpie, analyzing its different aspects and its impact on today's society. Additionally, we will examine how Black-billed magpie has evolved over time and what challenges and opportunities it presents in the future.

| Black-billed magpie | |

|---|---|

| |

| In Flagstaff County, Alberta | |

| Black-billed magpie vocalizations | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Corvidae |

| Genus: | Pica |

| Species: | P. hudsonia

|

| Binomial name | |

| Pica hudsonia (Sabine, 1823)

| |

| |

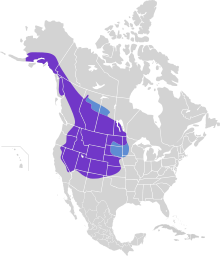

Year-round range Winter range

| |

The black-billed magpie (Pica hudsonia), also known as the American magpie, is a bird in the corvid family found in the western half of North America. It is black and white, with the wings and tail showing black areas and iridescent hints of blue and blue-green. It was once thought to be a subspecies of the Eurasian magpie (Pica pica), but was placed into its own species in 2000 based on genetic studies.

This species prefers generally open habitats with clumps of trees, but can also commonly be found in farmlands and suburban areas. Historically associated with bison herds, it now lands on the backs of cattle to glean ticks and insects from them. Black-billed magpies commonly follow large predators, such as wolves, to scavenge from their kills. The species also walks or hops on the ground, where it obtains food items such as beetles, grasshoppers, worms, and small rodents.

The black-billed magpie builds domed nests which are made up of twigs and are located near the top of trees, usually housing six to seven eggs. Incubation, by the female only, starts when the clutch is complete, and lasts 16–21 days. The nestling period is three to four weeks. Black-billed magpies in the wild have a lifespan of six to seven years.

Black-billed magpies have a long history with humans, being featured in stories told by Indigenous tribes of the Great Plains. Where persecuted it becomes very wary, but otherwise it is fairly tolerant of human presence. Due to their perceived negative impact on cattle and game birds, black-billed magpies were hunted as a pest during the 1900s, and their population suffered as a result. Today, they are considered a species of least concern by the IUCN, and they are commonly seen throughout their range.

Taxonomy and systematics

The black-billed magpie was originally described in 1823 as Corvus Hudsonius by Joseph Sabine. In previous encounters with the species prior to its description, it was presumed to be the Eurasian magpie (Pica pica) due to their visual similarities. Based on the black-billed magpie's smaller size and longer tail and wing length, it was classified as the subspecies P. pica hudsonia. The generic name Pica is the Latin word for magpie, and the specific name hudsonia is in honour of the English explorer Henry Hudson.

The word "magpie" comes from a combination of "Mag", which was a nickname for Margaret, and "pie", which was the Middle English word for the Eurasian magpie. The name Margaret was associated with chattiness in the early 15th century, and was applied to the magpie because its vocalizations were thought to sound like a person chattering.

The black-billed magpie was widely considered conspecific with the Eurasian magpie until mtDNA studies showed a relatively high divergence between the two species. It was also shown that the black-billed magpie was more closely related to California's yellow-billed magpie (Pica nuttalli). Black-billed magpies are also shown to have different social behaviours and vocalizations from the Eurasian magpie, further indicating separate species. In 2000, the American Ornithologists' Union recognized the black-billed magpie as a separate species, Pica hudsonia.

Fossil evidence suggests that the ancestral North American magpie arrived in its current range around the mid-Pliocene, approximately 3–4 mya (unit), having crossed the Bering land bridge. From there, the Eurasian and North American populations began to differentiate. The yellow-billed magpie lineage likely split off soon after due to the Sierra Nevada uplift and the beginning of an ice age. A comparatively low genetic difference, however, suggests that some gene flow between the black-billed and yellow-billed magpies still occurred during interglacial periods until the Pleistocene.

Description

The black-billed magpie is an unmistakable bird within its range. It is a medium-sized bird that measures 45–60 centimeters (18–24 in) from tip to tail. It is largely black, with white scapulars, belly, and primaries, and the wings and tail are an iridescent blue-green. The tail is made up of long, layered feathers, the middle pair of which extend further than the rest. The beak is uniformly black, oblong, and weakly curved toward the tip. Adults also have black irises.

Unlike other members of the Corvidae family, the black-billed magpie is dimorphic in size and weight, though there can be overlap between the sexes. Males are, on average, six to nine percent larger and sixteen to twenty-four percent heavier than females, at 167–216 grams (5.9–7.6 oz), an individual wing chord of 205–219 millimeters (8.1–8.6 in), and tail lengths of 230–320 millimeters (9.1–12.6 in). Females weigh between 141–179 grams (5.0–6.3 oz), have individual wing chords of 175–210 millimeters (6.9–8.3 in), and tail lengths of 232–300 millimeters (9.1–11.8 in).

Juveniles have less iridescence on their wings and tail, buffier scapulars and belly, and they lack the distinctive long tail feathers. Their rectrices are typically rounder and narrower, and have more black on their wing-tips compared to mature adults. They also have pink mouth-linings and grey irises. All juvenile features will typically be gone by the first year's moult.

The black-billed magpie can be distinguished from the similar yellow-billed magpie by its longer tail and by the colour of the beak. Eurasian magpies are visually very similar to black-billed magpies; however, Eurasian magpies are slightly larger and have shorter tails and wings. They can also be distinguished based on their different vocalizations, as well as by their non-overlapping ranges.

Vocalizations

The vocalizations of the black-billed magpie consist of a number of calls variously described as tweets, coos, purrs, shrills and squawks, but the most common is an alarm call, called a chatter, that is described as a ka-ka-ka-ka, sometimes preceded with a skah-skah. This call is very different from that of the Eurasian magpie and is similar to that of the yellow-billed magpie. At least one black-billed magpie, living with humans, has learned to imitate human speech.

Distribution and habitat

Black-billed magpies are generally non-migratory, however some winter movement does occur. While the exact reason for these movements is unknown, it is thought to be a result of postbreeding dispersal and a subsequent return to their nesting sites. This species ranges from coastal southern Alaska, southwest Yukon Territory, central British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba in the north, through the Rocky Mountains down south to all the Rocky Mountain states including New Mexico, Colorado, Utah, Wyoming, Idaho, and some bordering states as well. The range can extend as far east as northern Minnesota and Iowa, with casual records in northern Wisconsin and upper Michigan, but is thought to be limited further east and south by high temperature and humidity. The species is absent in California west of the Cascades and Sierra Nevada ranges, where it is replaced by the yellow-billed magpie.

During the breeding season the preferred habitat is riparian areas with thickets. The predilection for open habitats with clumps of trees means that the species lives in meadows and suburbs. Outside the breeding season, magpies can be found in their breeding habitat but also near feedlots, grain elevators, landfills, and around barns and houses.

Behaviour

Breeding and nesting

Adult black-billed magpie typically form pairs which last year-round and often for life, in which case the remaining magpie may find another mate. "Divorces" are possible; one South Dakota study found low rates of divorce (8%) but one study in Alberta found that pairs had a 63% divorce rate over a 7-year period.

Black-billed magpies nest individually, and often situate their nests near the top of trees. Only the nest tree and its immediate surroundings are defended, and so it is possible for nests to be somewhat clumped in a location. When this happens (usually in areas with a limited number of trees or with abundant food resources), a diffuse colony is formed. In this, the black-billed magpie is intermediate between the Eurasian magpie, whose nests are much more spread out because a large territory is defended around each nest, and the yellow-billed magpie, which is always loosely colonial.

Nests are loose but large accumulations of branches, twigs, grass, rootlets, mud, fur, and other materials. Branches and twigs constitute the base and framework, while mud is used as anchor and in the nest cup. The cup is lined with materials found nearby, often grass, rootlets, and other soft material. A hood or dome is present on almost all nests, and if formed of twigs and branches that are loosely assembled. The nest will usually have a single side entrance. Nests are built by both sexes over 40–50 days, starting in February (though later in northern parts of the range). Nests have been shown to be quite durable, and occasionally old nests are repaired and reused across multiple breeding seasons.

If regularly disturbed, black-billed magpie pairs will aggressively defend their nest. If the disturbances continue, they will eventually either move the eggs or abandon the clutch altogether. Biologists who have climbed nest trees to measure magpie eggs have reported that the parents recognized them personally on subsequent days and started to mob them, overlooking other people in the vicinity.

Black-billed magpies generally start breeding in late March, with the breeding season ending in early July. While they typically only nest once per year, a second nesting may take place if the initial nesting fails early. The average clutch size is six or seven eggs, however females may lay up to thirteen eggs. The eggs are greenish grey, marked with browns, and 33 mm (1.3 in) long. Incubation lasts 16–21 days and is done only by the female. Hatching is often asynchronous, and hatched young are altricial, brooded by the female but fed by both sexes. Juveniles are able to fly 3–4 weeks after hatching, and will feed with adults for about two months before leaving to join other juvenile magpies. Fledging success (usually 3–4 young per nest) is lower than the typical clutch size; this is not an unusual state of affairs in species with asynchronous hatching, as some nestlings often die of starvation. Black-billed magpies reach sexual maturity at one or two years of age. The lifespan of the species in the wild is about four to six years.

Feeding

The black-billed magpie is an opportunistic omnivore, eating whatever is readily available, including carrion, insects, seeds, berries, and nuts. When living near humans, they will also eat garbage and food from pets or livestock that are fed outside. They have been known to hunt rodents, reptiles, amphibians, small birds, and have also been seen eating eggs of other birds. Black-billed magpies primarily feed on animal matter during the summer, and in the winter switch to more vegetation. Chicks are fed animal matter almost exclusively. Magpies typically forage on the ground, scratching with their feet or beaks to turn over ground litter. They often follow large predators, such as wolves, to scavenge or steal from their kills. They sometimes land on large mammals, such as moose, cattle, or deer, to pick at the ticks that often plague these animals.

Black-billed magpies are also known to make food caches in the ground, in scatter-hoarding fashion. To make a cache, the bird pushes or hammers its bill into the ground (or snow), forming a small hole into which it deposits the food items it was holding in a small pouch under its tongue. It may, however, then move the food to another location, particularly if other magpies in the vicinity are watching. Cache robbing is fairly common, so a magpie often makes several false caches before a real one. The final cache is covered with grass, leaves, or twigs. After this, the bird cocks its head and stares at the cache, possibly to commit the site to memory. Such hoards are short-term; the food is usually recovered within several days, or the bird never returns. The bird relocates its caches by sight and also by smell; during cache robbing, smell is probably the primary cue.

Social interactions

Black-billed magpies often form loose flocks outside of the breeding season. Dominance hierarchies typically develop within such flocks, more linearly among males than among females. Dominants can steal food from subordinates. Aggressive interactions also occur at point sources of food. Surprisingly, young males appear dominant over adult males, though this may simply reflect the adults' lack of motivation to engage in fights as they can more easily find food. Fights are rare and involve jumps and kicks. Dominance is more generally established through displays, such as stretching the body laterally with the bill raised and the nictitating membrane of the eye flashing (only on the side of the opponent).

Magpies often gather excitedly in trees near the body of a dead magpie, calling loudly, a poorly-understood behaviour called a funeral.

Roosting

Magpies tend to roost communally in winter. Every evening they fly, often in groups and sometimes over long distances, to reach safe roosting sites such as dense trees or shrubs that impede predator movement, or, at higher latitudes, dense conifers that afford good wind protection. In Canada, they arrive at the roosting site earlier in the evening and leave later in the morning on colder days. At the roosting site, they tend to occupy trees singly; they do not huddle. They sleep with the bill tucked under the scapular (shoulder) and back feathers, adopting this position sooner on colder nights. During the night, they may also regurgitate in the form of pellets the undigested parts of what they ate during the day. Such pellets can be found on the ground and then used to determine at least part of the birds' diet.

Flight

Level flight appears slow and labored. As measured in wind tunnels, minimum and maximum sustained flight speeds are 14.5 and 50 km/h (9 and 31 mph), respectively. Flight is commonly interrupted by nonflapping phases. Descents from heights consist of repeated J-shaped swoops with the wings nearly closed.

Relationship with humans

Black-billed magpies feature in stories told by various Indigenous tribes from the Great Plains. One story, sometimes known as "The Great Race", features a magpie working with humans in a race against the bison to determine who would be hunter and who would be prey. The race was narrowly won by the magpie, who had clung to the back of the bison until near the end, making humans the hunters and bison the hunted.

When Lewis and Clark first encountered black-billed magpies in 1804 in South Dakota, they reported the birds as being very bold, entering tents and taking food from the hand. Magpies formerly followed American bison herds, from which they would glean ticks and other insects, as well as the Indigenous tribes that hunted the bison so they could scavenge carcasses. When the bison herds were devastated in the 1870s, magpies switched to cattle, and by the 1960s, they had also moved into the emerging towns and cities of the West. Today, black-billed magpies remain relatively tame in areas where they are not hunted. However, they become very wary in areas where they are often shot at or disturbed. Black-billed magpies were thought to be harmful to the population of game birds (due to them sometimes stealing bird eggs) and domestic stock (pecking at sores on cattle), and were systematically trapped or shot during the first half of the 20th century. Bounties of one cent per egg or two cents per head were offered in many states. In 1933, bounty hunters in the Okanogan valley in Washington shot 1,033 magpies. Magpies also died as a result of eating poison set out for predators.

Black-billed magpies are considered a pest by some because of their reputation for stealing songbird eggs. Studies have shown, however, that eggs make up only a small proportion of what magpies feed on during the reproductive season, and that songbird populations do not fare worse in the presence of magpies.

A common misconception about magpies in general is that they like to steal bright or shiny things. This reputation belongs to the Eurasian magpie (Pica pica) rather than the black-billed magpie, and at any rate an experiment conducted at Exeter University has shown that the reputation is undeserved. Eurasian magpies displayed caution around shiny objects rather than being attracted to them.

Conservation status

Because of its wide range and generally stable population, the black-billed magpie is rated as a species of least concern by the International Union for Conservation of Nature. As of 2015, the Government of Canada estimates the population to be between 500,000 and 5,000,000 adults.

In the United States, black-billed magpies are protected under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, but " Federal permit shall not be required to control ... when found committing or about to commit depredations upon ornamental or shade trees, agricultural crops, livestock, or wildlife, or when concentrated in such numbers and manner as to constitute a health hazard or other nuisance". State or local regulations may limit or prohibit killing these birds as well.

In Canada, however, black-billed magpies do not appear on the list of birds protected by the Migratory Birds Convention Act. Provincial laws also apply, but in Alberta, magpies may be hunted and trapped without a license.

A detriment to the overall black-billed magpie population is toxic chemicals, particularly topical pesticides applied on the backs of livestock. Because black-billed magpies sometimes glean ticks off the backs of cattle, this proves a problem. However, in some areas, it has benefited from forest fragmentation and agricultural developments. Like many corvids, it is susceptible to West Nile virus.

References

- ^ a b BirdLife International (2017) . "Pica hudsonia". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2017: e.T103727176A111465610. Retrieved November 19, 2021.

- ^ Franklin, John (1823). Narrative of a journey to the shores of the Polar Sea, in the years 1819, 20, 21, and 22. London: J Murray. pp. 671–672. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.46471. ISBN 066535178X. Retrieved November 15, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Charles H. Trost (2020). Billerman, Shawn M (ed.). "Black-billed magpie (Pica hudsonia)". Birds of the World Online (S.M. Billerman, Ed.). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. doi:10.2173/bow.bkbmag1.01. Retrieved July 11, 2022.

- ^ "Etymology of magpie". www.etymonline.com. Retrieved January 12, 2024.

- ^ Zink, R.M.; Rohwer, S.; Andreev, A.V.; Dittman, D.L. (1995). "Trans-Beringia comparisons of mitochondrial DNA differentiation in birds" (PDF). Condor. 97 (3): 639–649. doi:10.2307/1369173. JSTOR 1369173. Retrieved November 15, 2023.

- ^ a b Peter Enggist-Düblin & Tim Robert Birkhead (1992). "Differences in the Calls of European and North American Black-billed Magpies and Yellow-billed Magpies". Bioacoustics. 4: 185–94. doi:10.1080/09524622.1992.9753220.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Birkhead, T.R. (1991). The magpies: The ecology and behaviour of Black-billed and Yellow-billed Magpies. Academic Press, London. ISBN 0-85661-067-4.

- ^ Banks, Richard C.; Cicero, Carla; Kratter, Andrew W.; Ouellet, Henri; Rasmussen, Pamela C.; Remsen, J. V.; Stotz, Douglas F. (July 2000). "Forty-Second Supplement to the American Ornithologists' Union Check-List of North American Birds". The Auk. 117 (3): 847–858. doi:10.2307/4089622. JSTOR 4089622.

- ^ Miller, Alden H. & Bowman, Robert I. (1956). "A fossil magpie from the Pleistocene of Texas" (PDF). Condor. 58 (2): 164–165. doi:10.2307/1364980. JSTOR 1364980.

- ^ Reese, K.P.; Kadlex, J.A. (1982). "Determining the sex of Black-billed Magpies by external measurements" (PDF). Journal of Field Ornithology. 53: 417–418. Retrieved November 15, 2023.

- ^ Erpino, Michael J. (1968). "Age Determination in the Black-Billed Magpie". Condor. 70 (1): 91–92. doi:10.2307/1366522. JSTOR 1366522. Retrieved December 31, 2023.

- ^ "This Talking magpie is Amazing!". YouTube.

- ^ Bock, C.E. & Lepthien, L.W. (1975). "Distribution and abundance of the Black-billed magpie (Pica pica) in North America". Great Basin Naturalist. 35 (3): 269–272. JSTOR 41711476.

- ^ Hayworth, A.M. & W.W. Weathers (1984). "Temperature regulation and climatic adaptation in Black-billed and Yellow-billed Magpies". Condor. 86 (1): 19–26. doi:10.2307/1367336. JSTOR 1367336.

- ^ Buitron, D. (1988). "Female and male specialization in parental care and its consequences in Black-billed magpies". Condor. 90 (1): 29–39. doi:10.2307/1368429. JSTOR 1368429.

- ^ Dhindsa, M.S. & Boag, D.A. (1992). "Patterns of nest site, territory and mate switching in Black-billed Magpies". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 70 (4): 633–640. doi:10.1139/z92-095.

- ^ a b c Erpino, M. J. (1968). "Nest-related Activities of Black-billed Magpies" (PDF). The Condor. 70 (2): 154–165. doi:10.2307/1365958. JSTOR 1365958. Retrieved January 9, 2024.

- ^ Buitron, D. (1983). "Extra-pair courtship in Black-billed Magpies". Animal Behaviour. 31: 211–220. doi:10.1016/S0003-3472(83)80191-2. S2CID 53168821.

- ^ Genov, Peter V.; Gigantesco, Paola; Massei, Giovanna (February 1998). "Interactions between Black-Billed Magpie and Fallow Deer". The Condor. 100 (1): 177–179. doi:10.2307/1369914. JSTOR 1369914.

- ^ Hendricks, Paul (2020). "Black-billed Magpies (Pica hudsonia) caching food in snow". Northwestern Naturalist. 101 (2): 125–129. doi:10.1898/1051-1733-101.2.125. S2CID 220922618. Retrieved January 24, 2024.

- ^ Buitron, D. & Nuechterlein, G.L. (1985). "Experiments on olfactory detection of food caches by black-billed magpies". Condor. 87 (1): 92–95. doi:10.2307/1367139. JSTOR 1367139.

- ^ a b Trost, C.H. & Webb C. L. (1997). "The effect of sibling competition on the subsequent social status of juvenile North American Black-billed Magpies (Pica pica hudsonia)". Acta Ornithologica. 32: 111–119.

- ^ Komers, P.E. (1989). "Dominance relationships between juvenile and adult Black-billed Magpies". Animal Behaviour. 37: 256–265. doi:10.1016/0003-3472(89)90114-0. S2CID 53163369.

- ^ Reebs, S.G. (1987). "Roost characteristics and roosting behaviour of Black-billed Magpies, Pica pica, in Edmonton, Alberta". Canadian Field-Naturalist. 101: 519–525.

- ^ Reebs, S.G. (1986). "Influence of temperature and other factors on the daily roosting times of black-billed magpies". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 64 (8): 1614–1619. doi:10.1139/z86-243.

- ^ Reebs, S.G. (1986). "Sleeping behavior of Black-billed Magpies under a wide range of temperatures". Condor. 88 (4): 524–526. doi:10.2307/1368284. JSTOR 1368284.

- ^ Reebs, S.G. & Boag, D.A. (1987). "Regurgitated pellets and late winter diet of Black-billed Magpies, Pica pica, in central Alberta". Canadian Field-Naturalist. 101: 108–110.

- ^ Tobalske, B.W.; Dial, K.P. (1996). "Flight kinematics of Black-billed Magpies and pigeons over a wide range of speeds". Journal of Experimental Biology. 99 (Pt 2): 263–280. doi:10.1242/jeb.199.2.263. PMID 9317775.

- ^ Pierotti, Raymond (December 4, 2020). "Learning about Extraordinary Beings: Native Stories and Real Birds". Ethnobiology Letters. 11 (2): 44–51. doi:10.14237/ebl.11.2.2020.1640. hdl:1808/34656.

- ^ Ryser, S.A. (1985). Birds of the Great Basin: A Natural History. University of Nevada Press. ISBN 978-0-87417-080-1.

- ^ a b c Houston, C.S. (1977). "Changing patterns of Corvidae on the prairies". Blue Jay. 35 (3): 149–156. doi:10.29173/bluejay4262. Retrieved December 17, 2023.

- ^ Link, Russell (2005). "Living with Wildlife - Magpie" (PDF). Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife. Retrieved December 21, 2023.

- ^ Shephard, T.V.; Lea, S.E.G.; Hempel de Ibarra, N. (2015). "The thieving magpie? No evidence for attraction to shiny objects". Animal Cognition. 18 (1): 393–397. doi:10.1007/s10071-014-0794-4. hdl:10871/16723. PMID 25123853. S2CID 717341.

- ^ "Black-billed Magpie (Pica hudsonia)". wildlife-species.canada.ca. Government of Canada. August 19, 2015. Retrieved December 21, 2023.

- ^ Title 50 Code of Federal Regulations Section 21.43. gpo.gov

- ^ Birds protected under the Migratory Birds Convention Act Archived 2019-05-20 at the Wayback Machine canada.ca

- ^ Alberta Wildlife Act, Schedule 4, Part 6 Non‑licence Animals qp.alberta.ca

- ^ Taylor, Daniel M.; Trost, Charles H. (November 26, 2021). "West Nile Virus Impacts on Black-Billed Magpie Populations". Northwestern Naturalist. 102 (3): 239–251. doi:10.1898/1051-1733-102.3.239. S2CID 244661736.

Further reading

- Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, Living with Wildlife; Facts about Magpies

- Black-billed magpie species account—Cornell Lab of Ornithology

- Black-billed magpie—Birds of the world

External links

- Black-billed magpie photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)