Japanese sword

The name Japanese sword evokes different emotions and opinions in people. From admiration and respect to rejection and indifference, Japanese sword has been a source of debate and interest over time. In this article, we will explore the different facets and perspectives related to Japanese sword, from its origin and meaning to its relevance today. Through detailed analysis, we seek to shed light on this topic and provide a complete and objective view that invites reflection and understanding.

A Japanese sword (Japanese: 日本刀, Hepburn: nihontō) is one of several types of traditionally made swords from Japan. Bronze swords were made as early as the Yayoi period (1,000 BC–300 AD), though most people generally refer to the curved blades made from the Heian period (794–1185) to the present day when speaking of "Japanese swords". There are many types of Japanese swords that differ by size, shape, field of application and method of manufacture. Some of the more commonly known types of Japanese swords are the uchigatana, tachi, ōdachi, wakizashi, and tantō.

Classification

Classification by shape and usage

In modern times the most commonly known type of Japanese sword is the Shinogi-Zukuri katana, which is a single-edged and usually curved longsword traditionally worn by samurai from the 15th century onwards. Western historians have said that Japanese katana were among the finest cutting weapons in world military history, for their intended use.

Other types of Japanese swords include: tsurugi or ken, which is a straight double-edged sword; ōdachi, tachi, which are older styles of a very long curved single-edged sword; uchigatana, a slightly shorter curved single-edged long sword; wakizashi, a medium-sized sword; and tantō, which is an even smaller knife-sized sword. Naginata, nagamaki, and yari, despite being polearms, are still considered to be swords, which is a common misconception; naginata, nagamaki, yari and even ōdachi are in reality not swords.

The type classifications for Japanese swords indicate the combination of a blade and its mounts as this, then, determines the style of use of the blade. An unsigned and shortened blade that was once made and intended for use as a tachi may be alternately mounted in tachi koshirae and katana koshirae. It is properly distinguished, then, by the style of mount it currently inhabits. A long tanto may be classified as a wakizashi due to its length being over 30 cm (12 in), however it may have originally been mounted and used as a tanto making the length distinction somewhat arbitrary but necessary when referring to unmounted short blades. When the mounts are taken out of the equation, a tanto and wakizashi will be determined by length under or over 30 cm (12 in), unless their intended use can be absolutely determined or the speaker is rendering an opinion on the intended use of the blade. In this way, a blade formally attributed as a wakizashi due to length may be informally discussed between individuals as a tanto because the blade was made during an age where tanto were popular and the wakizashi as a companion sword to katana did not yet exist.[citation needed]

The following are types of Japanese swords:

- Tsurugi/Ken (剣, "sword"): A straight two edged sword that was mainly produced prior to the 10th century. After the 10th century, they completely disappeared as weapons and came to be made only as offerings to Shinto shrines and Buddhist temples.

- Chokutō (直刀, "straight sword"): A straight single edged sword that was mainly produced prior to the 10th century. Since the 10th century, they disappeared as weapons and came to be made only as offerings to Shinto shrines and Buddhist temples.

- Tachi (太刀, "long sword"): A sword that is generally longer and more curved than the later katana, with curvature often centered from the middle or towards the tang, and often including the tang. Tachi were worn suspended, with the edge downward. The tachi was in vogue before the 15th century.

- Kodachi (小太刀, "small Tachi"): A shorter version of the tachi, but with similar mounts and intended use, mostly found in the 13th century or earlier.

- Ōdachi (大太刀, "large Tachi")/Nodachi (野太刀, "field Tachi"): A longer version of the tachi, generally with a blade length of more than 90 cm (35 in), mostly found in the 14th century or later.

- Uchigatana (打刀, "striking sword"): A sword with a curved blade longer than 60 cm (24 in) (there is no upper length limit but generally they are shorter than 90 cm (35 in)), worn with the edge upwards in the sash. It was developed from sasuga, a kind of tantō, around the 14th century, and became the mainstream replacing tachi from the 15th century onwards.

- Wakizashi (脇差, "side inserted "): A general term for a sword between one and two shaku long (30 cm (12 in) and 60 cm (24 in) in modern measurements), predominantly made after 1600. Generally it is the short blade that accompanies a katana in the traditional samurai daisho pairing of swords, but may be worn by classes other than the samurai as a single blade, also worn edge up as the katana. The name derives from the way the sword would be stuck at one's side through the sash.

- Tantō (短刀, "short blade"): A sword with a blade shorter than one shaku (30 cm (12 in)). Tantō are generally classified as a sword, but its usage is the same as that of a knife. Usually one-edged, but some were double-edged, though asymmetrical.

There are other bladed weapons made in the same traditional manner as Japanese swords, which are not swords, but are still classified as Japanese swords (nihontō) (as "tō" means "blade", rather than specifically "sword") because of the way they are made in a similar manner to Japanese swords:

- Nagamaki (長巻, "long wrapping"): A sword with an exceptionally long handle, usually about as long as the blade. The name refers to the length of the handle wrapping.

- Naginata (なぎなた, 薙刀): A polearm with a curved single-edged blade. Naginata mounts consist of a long wooden pole, different from a nagamaki mount, which is shorter and wrapped.

- Yari (槍, "spear"): A spear, or spear-like polearm. Yari have various blade forms, from a simple double edged and flat blade, to a triangular cross section double edged blade, to those with a symmetric cross-piece (jumonji-yari) or those with an asymmetric cross piece. The main blade is symmetric and straight, unlike a naginata, and usually smaller, but can be as large as or bigger than some naginata blades.

Other edged weapons or tools that are made using the same methods as Japanese swords:

- Arrowheads for war, yajiri (or yanone).

- Kogatana (小刀, "small blade"): An accessory or utility knife, sometimes found mounted in a pocket on the side of the scabbard of a sword. A typical blade is about 10 cm (3.9 in) long and 1 cm (0.39 in) wide, and is made using the same techniques as the larger sword blades. Also referred to as a "Kozuka" (小柄), which literally means 'small handle', but this terminology can also refer to the handle and the blade together. In entertainment media, the kogatana is sometimes shown as a throwing weapon, but its real purpose was the same as a 'pocket knife' in the West.

Classification by period

Each Japanese sword is classified according to when the blade was made.:

- Jōkotō (上古刀 "ancient swords", until around 900 A.D.)

- Kotō (古刀"old swords" from around 900–1596)

- Shintō (新刀 "new swords" 1596–1780)

- Shinshintō (新々刀 "new new swords" 1781–1876)

- Gendaitō (現代刀 "modern or contemporary swords" 1876– present)

Historically in Japan, the ideal blade of a Japanese sword has been considered to be the kotō in the Kamakura period, and the swordsmiths from the Edo period to the present day from the Shinto period focused on reproducing the blade of a Japanese sword in the Kamakura period. There are more than 100 Japanese swords designated as National Treasures in Japan, of which the Kotō of the Kamakura period account for 80% and the tachi account for 70%.

Japanese swords since shintō are different from kotō in forging method and steel. This was due to the destruction of the Bizen school due to a great flood, the spread of the Mino school, and the virtual unification of Japan by Toyotomi Hideyoshi, which made almost no difference in the steel used by each school. Japanese swords since the Shintō period often have gorgeous decorations carved on the blade and lacquered maki-e decorations on the scabbard. This was due to the economic development and the increased value of swords as arts and crafts as the Sengoku Period ended and the peaceful Edo Period began.

Japanese swords are still commonly seen today; antique and modern forged swords can be found and purchased. Modern, authentic Japanese swords (nihontō) are made by a few hundred swordsmiths. Many examples can be seen at an annual competition hosted by the All Japan Swordsmith Association, under the auspices of the Nihontō Bunka Shinkō Kyōkai (Society for the Promotion of Japanese Sword Culture). However, in order to maintain the quality of Japanese swords, the Japanese government limits the number of Japanese swords a swordsmith can make in a year to 24 (up to 2 swords per month). Therefore, many of the swords called "Japanese sword" distributed around the world today are made in China, and the manufacturing process and quality are not authorized.

Classification by school

Many old Japanese swords can be traced back to one of five provinces, each of which had its own school, traditions, and "trademarks" (e.g., the swords from Mino province were "from the start famous for their sharpness"). These schools are known as Gokaden (The Five Traditions). In the Kotō era there were several other schools that did not fit within the Five Traditions or were known to mix elements of each Gokaden, and they were called wakimono (small school). There were 19 commonly referenced wakimono. The number of swordsmiths of Gokaden, as confirmed by signatures and documents, were 4005 in Bizen, 1269 in Mino, 1025 in Yamato, 847 in Yamashiro and 438 in Sōshū. These traditions and provinces are as follows:

Yamato School

The Yamato school is a school that originated in Yamato Province corresponding to present-day Nara Prefecture. Nara was the capital of ancient Japan. Since there is a legend that it was a swordsmith named Amakuni who first signed the tang of a sword, he is sometimes regarded as the founder and the oldest school. However, the founder identified in the material is Yukinobu in the Heian period. They forged the swords that were often worn by monk warriors called sōhei in Nara's large temples. The Yamato school consists of five schools: Senjuin, Shikkake, Taima, Tegai, and Hōshō. Each school forged swords under the supervision of a different temple. In the middle of the Muromachi period, swordsmiths moved to various places such as Mino, and the school disappeared. Their swords are often characterized by a deep curve, a narrow width from blade to back, a high central ridge, and a small tip. There are direct lines on the surface of the blade, the hamon is linear, and the grain at the boundary of the hamon is medium in size. It is often evaluated as a sword with a simple and strong impression.

Yamashiro School

The Yamashiro school is a school that originated in Yamashiro Province, corresponding to present-day Kyoto Prefecture. When Emperor Kanmu relocated the capital to Kyoto in 794, swordsmiths began to gather. The founder of the school was Sanjō Munechika in the late 10th century in the Heian period. The Yamashiro school consisted of schools such as Sanjō, Ayanokōji, Awataguchi, and Rai. At first, they often forged swords in response to aristocrats' demands, so importance was placed on aesthetics and practicality was not emphasized. However, when a domestic conflict occurred at the end of the Heian period, practicality was emphasized and a swordsmith was invited from the Bizen school. In the Kamakura period, tachi from a magnificent rai school became popular among samurai. After that, they also adopted the forging method of Sōshū school. Their swords are often characterized as long and narrow, curved from the base or center, and have a sparkle on the surface of the blade, with the hamon being straight and the grains on the boundary of the hamon being small. It is often evaluated as a sword with an elegant impression.

Bizen School

The Bizen school is a school that originated in Bizen Province, corresponding to present-day Okayama Prefecture. Bizen has been a major production area of high quality iron sand since ancient times. The Ko-bizen school in the mid Heian period was the originator. The Bizen school consisted of schools such as Ko-bizen, Fukuoka-ichimonji, Osafune, and Hatakeda. According to a sword book written in the Kamakura period, out of the 12 best swordsmiths in Japan who were convened by the Retired Emperor Go-Toba, 10 were from the Bizen school. Great swordsmiths were born one after another in the Osafune school which started in the Kamakura period, and it developed to the largest school in the history of Japanese swords. Kanemitsu and Nagayoshi of the Osafune school were apprentices to Masamune of the Sōshū school, the greatest swordsmith in Japan. While they forged high-quality swords by order, at the same time, from the Muromachi period, when wars became large-scale, they mass-produced low-quality swords for drafted farmers and for export. The Bizen school had enjoyed the highest prosperity for a long time, but declined rapidly due to a great flood which occurred in the late 16th century during the Sengoku period. Their swords are often characterized as curved from the base, with irregular fingerprint-like patterns on the surface of the blade, while the hamon has a flashy pattern like a series of cloves, and there is little grain but a color gradient at the boundary of the hamon. It is often evaluated as a sword with a showy and gorgeous impression.

Sōshū School

The Sōshū school is a school that originated in Sagami Province, corresponding to present-day Kanagawa Prefecture. Sagami Province was the political center of Japan where the Kamakura shogunate was established in the Kamakura period. At the end of the 13th century, the Kamakura shogunate invited swordsmiths from Yamashiro school and Bizen school, and swordsmiths began to gather. Shintōgo Kunimitsu forged experimental swords by combining the forging technology of Yamashiro school and Bizen school. Masamune, who learned from Shintōgo Kunimitsu, became the greatest swordsmith in Japan. From the lessons of the Mongol invasion of Japan, they revolutionized the forging process to make stronger swords. Although this forging method is not fully understood to date, one of the elements is heating at higher temperatures and rapid cooling. Their revolution influenced other schools to make the highest quality swords, but this technique was lost before the Azuchi–Momoyama period (Shintō period). The Sōshū school declined after the fall of the Kamakura shogunate. Their swords are often characterized by a shallow curve, a wide blade to the back, and a thin cross-section. There are irregular fingerprint-like patterns on the surface of the blade, the hamon has a pattern of undulations with continuous roundness, and the grains at the boundary of the hamon are large.

Mino School

The Mino school is a school that originated in Mino Province, corresponding to present-day Gifu Prefecture. Mino Province was a strategic traffic point connecting the Kanto and Kansai regions, and was surrounded by powerful daimyo (feudal lords). The Mino school started in the middle of the Kamakura period, when swordsmiths of the Yamato school who learned from the Sōshū school gathered in Mino. The Mino school became the largest production area of Japanese swords after the Bizen school declined due to a great flood. The production rate of katana was high, because it was the newest school among 5 big schools. Their swords are often characterized by a slightly higher central ridge and a thinner back. There are irregular fingerprint-like patterns on the surface of the blade, the hamon are various, and the grain on the border of the hamon are hardly visible.

Etymology

The word katana was used in ancient Japan and is still used today, whereas the old usage of the word nihontō is found in the poem the Song of Nihontō, by the Song dynasty poet Ouyang Xiu. The word nihontō became more common in Japan in the late Tokugawa shogunate. Due to importation of Western swords, the word nihontō was adopted in order to distinguish it from the Western sword (洋刀, yōtō).[citation needed]

Meibutsu (noted swords) is a special designation given to sword masterpieces which are listed in a compilation from the 18th century called the "Kyoho Meibutsucho". The swords listed are Koto blades from several different provinces; 100 of the 166 swords listed are known to exist today, with Sōshū blades being very well represented. The "Kyoho Meibutsucho" also listed the nicknames, prices, history and length of the Meibutsu, with swords by Yoshimitsu, Masamune, Yoshihiro, and Sadamune being very highly priced.

Anatomy

Blade

Each blade has a unique profile, mostly dependent on the swordsmith and the construction method. The most prominent part is the middle ridge, or shinogi. In the earlier picture, the examples were flat to the shinogi, then tapering to the blade edge. However, swords could narrow down to the shinogi, then narrow further to the blade edge, or even expand outward towards the shinogi then shrink to the blade edge (producing a trapezoidal shape). A flat or narrowing shinogi is called shinogi-hikushi, whereas a flat blade is called a shinogi-takushi.

The shinogi can be placed near the back of the blade for a longer, sharper, more fragile tip or a more moderate shinogi near the center of the blade.

The sword also has an exact tip shape, which is considered an extremely important characteristic: the tip can be long (ōkissaki), medium (chūkissaki), short (kokissaki), or even hooked backwards (ikuri-ōkissaki). In addition, whether the front edge of the tip is more curved (fukura-tsuku) or (relatively) straight (fukura-kareru) is also important.

The kissaki (point) is not usually a "chisel-like" point, and the Western knife interpretation of a "tantō point" is rarely found on true Japanese swords; a straight, linearly sloped point has the advantage of being easy to grind, but less stabbing/piercing capabilities compared to traditional Japanese kissaki Fukura (curvature of the cutting edge of tip) types. Kissaki usually have a curved profile, and smooth three-dimensional curvature across their surface towards the edge—though they are bounded by a straight line called the yokote and have crisp definition at all their edges. While the straight tip on the "American tanto" is identical to traditional Japanese fukura, two characteristics set it apart from Japanese sword makes: The absolute lack of curve only possible with modern tools, and the use of the word "tanto" in the nomenclature of the western tribute is merely a nod to the Japanese word for knife or short sword, rather than a tip style.

Although it is not commonly known, the "chisel point" kissaki originated in Japan. Examples of such are shown in the book "The Japanese Sword" by Kanzan Sato. Because American bladesmiths use this design extensively it is a common misconception that the design originated in America.

A hole is punched through the tang nakago, called a mekugi-ana. It is used to anchor the blade using a mekugi, a small bamboo pin that is inserted into another cavity in the handle tsuka and through the mekugi-ana, thus restricting the blade from slipping out. To remove the handle one removes the mekugi. The swordsmith's signature mei is carved on the tang.

Mountings

In Japanese, the scabbard is referred to as a saya, and the handguard piece, often intricately designed as an individual work of art—especially in later years of the Edo period—was called the tsuba. Other aspects of the mountings (koshirae), such as the menuki (decorative grip swells), habaki (blade collar and scabbard wedge), fuchi and kashira (handle collar and cap), kozuka (small utility knife handle), kogai (decorative skewer-like implement), saya lacquer, and tsuka-ito (professional handle wrap, also named tsukamaki), received similar levels of artistry.

Signature and date

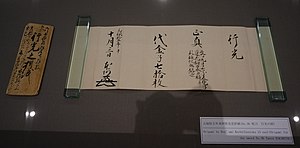

The mei is the signature inscribed on to the tang of the Japanese sword. Fake signatures ("gimei") are common not only due to centuries of forgeries but potentially misleading ones that acknowledge prominent smiths and guilds, and those commissioned to a separate signer.

Sword scholars collect and study oshigata, or paper tang-rubbings, taken from a blade: to identify the mei, the hilt is removed and the sword is held point side up. The mei is chiseled onto the tang on the side which traditionally faces away from the wearer's body while being worn; since the katana and wakizashi are always worn with the cutting edge up, the edge should be held to the viewer's left. The inscription will be viewed as kanji on the surface of the tang: the first two kanji represent the province; the next pair is the smith; and the last, when present, is sometimes a variation of 'made by', or, 'respectfully'. The date will be inscribed near the mei, either with the reign name; the Zodiacal Method; or those calculated from the reign of the legendary Emperor Jimmu, dependent upon the period.

Length

What generally differentiates the different swords is their length. Japanese swords are measured in units of shaku. Since 1891, the modern Japanese shaku is approximately equal to a foot (11.93 inches), calibrated with the meter to equal exactly 10 meters per 33 shaku (30.30 cm).

However, the historical shaku was slightly longer (13.96 inches or 35.45 cm). Thus, there may sometimes be confusion about the blade lengths, depending on which shaku value is being assumed when converting to metric or U.S. customary measurements.

The three main divisions of Japanese blade length are:

- Less than 1 shaku for tantō (knife or dagger).

- Between 1 and 2 shaku for shōtō (小刀:しょうとう) (wakizashi or kodachi).

- Greater than 2 shaku for daitō (大刀) (long sword, such as katana or tachi).

A blade shorter than one shaku is considered a tantō (knife). A blade longer than one shaku but less than two is considered a shōtō (short sword). The wakizashi and kodachi are in this category. The length is measured in a straight line across the back of the blade from tip to munemachi (where blade meets tang). Most blades that fall into the "shōtō" size range are wakizashi. However, some daitō were designed with blades slightly shorter than 2 shaku. These were called kodachi and are somewhere in between a true daitō and a wakizashi. A shōtō and a daitō together are called a daishō (literally, "big-little"). The daishō was the symbolic armament of the Edo period samurai.

A blade longer than two shaku is considered a daitō, or long sword. To qualify as a daitō the sword must have a blade longer than 2 shaku (approximately 24 inches or 60 centimeters) in a straight line. While there is a well defined lower limit to the length of a daitō, the upper limit is not well enforced; a number of modern historians, swordsmiths, etc. say that swords that are over 3 shaku in blade length are "longer than normal daitō" and are usually referred to as ōdachi.[citation needed] The word "daitō" is often used when explaining the related terms shōtō (short sword) and daishō (the set of both large and small sword). Miyamoto Musashi refers to the long sword in The Book of Five Rings. He is referring to the katana in this, and refers to the nodachi and the odachi as "extra-long swords".

Before about 1500 most swords were usually worn suspended from cords on a belt, edge-down. This style is called jindachi-zukuri, and daitō worn in this fashion are called tachi (average blade length of 75–80 cm). From 1600 to 1867, more swords were worn through an obi (sash), paired with a smaller blade; both worn edge-up. This style is called buke-zukuri, and all daitō worn in this fashion are katana, averaging 70–74 cm (2 shaku 3 sun to 2 shaku 4 sun 5 bu) in blade length. However, Japanese swords of longer lengths also existed, including lengths up to 78 cm (2 shaku 5 sun 5 bu).

It was not simply that the swords were worn by cords on a belt, as a 'style' of sorts. Such a statement trivializes an important function of such a manner of bearing the sword.[citation needed] It was a very direct example of 'form following function.' At this point in Japanese history, much of the warfare was fought on horseback. Being so, if the sword or blade were in a more vertical position, it would be cumbersome, and awkward to draw. Suspending the sword by 'cords' allowed the sheath to be more horizontal, and far less likely to bind while drawing it in that position.[citation needed]

Abnormally long blades (longer than 3 shaku), usually carried across the back, are called ōdachi or nodachi. The word ōdachi is also sometimes used as a synonym for Japanese swords. Odachi means "great sword", and Nodachi translates to "field sword". These greatswords were used during war, as the longer sword gave a foot soldier a reach advantage. These swords are now illegal in Japan. Citizens are not allowed to possess an odachi unless it is for ceremonial purposes.

Here is a list of lengths for different types of blades:

- Nodachi, Ōdachi, Jin tachi: 90.9 cm and over (more than three shaku)

- Tachi, Katana: over 60.6 cm (more than two shaku)

- Wakizashi: between 30.3 and 60.6 cm (between one and two shaku)

- Tantō, Aikuchi: under 30.3 cm (less than one shaku)

Blades whose length is next to a different classification type are described with a prefix 'O-' (for great) or 'Ko-' (for small), e.g. a Wakizashi with a length of 59 cm is called an O-wakizashi (almost a Katana) whereas a Katana of 61 cm is called a Ko-Katana (for small Katana; but note that a small accessory blade sometimes found in the sheath of a long sword is also a "kogatana" (小刀)).

Since 1867, restrictions and/or the deconstruction of the samurai class meant that most blades have been worn jindachi-zukuri style, like Western navy officers. Since 1953, there has been a resurgence in the buke-zukuri style, permitted only for demonstration purposes.

History

The production of swords in Japan is divided into specific time periods: jōkotō (ancient swords, until around 900 A.D.), kotō (old swords from around 900–1596), shintō (new swords 1596–1780), shinshintō (new new swords 1781–1876), gendaitō (modern or contemporary swords 1876–present)

Jōkotō – Kotō (Old swords)

Early examples of iron swords were straight tsurugi, chokutō and others with unusual shapes, some of the styles and techniques were derived from Chinese dao, and some directly imported through trade. The swords of this period were a mixture of swords of Japanese original style and those of Chinese style brought to Japan via the Korean Peninsula and East China Sea. The cross-sectional shape of the blades of these early swords was an isosceles triangular hira-zukuri, and the kiriha-zukuri sword, which sharpened only the part close to the cutting edge side of a planar blade, gradually appeared. Swords of this period are classified as jōkotō and are often referred to in distinction from Japanese swords.

The direct predecessor of the tachi (太刀) has been called Warabitetō (ja:蕨手刀) by the Emishi (Not to be confused with Ainu) of Tohoku. The Nihonto Meikan shows the earliest and by far the largest group of Ōshū smiths from the beginning of the 8th century were from the Mokusa school, listing over 100 Mokusa smiths before the beginning of the Kamakura period. Archaeological excavations of the Ōshū Tohoku region show iron ore smelting sites dating back to the early Nara period. The Tohoku region and indeed the whole Ōshū district in the 8th century was controlled and populated by the Emishi. Archaeological evidence of recovered Warabitetō (蕨手刀) show a high concentration in the burial goods of the Ōshū and Hokkaido regions. Mokusa Area was famous for legendary swordsmiths in the Heian Period (AD 794–1185). They are considered as the original producers of the Japanese swords known as "Warabitetō " which can date back to the sixth to eighth centuries. "Warabitetō " gained its fame through the series of battles between Emishi people (蝦夷) and the Yamato-chotei government (大 和朝廷) in the late eighth century. Using "Warabitetō," the small number of Emishi soldiers could resist against the numerous Yamato-chotei army over a Thirty-Eight Years' War (三十八年戦争) (AD 770–811). The Meikan describes that from earlier time there was a list of forty two famous swordsmiths in the Toukou Meikan 刀工銘鑑 at Kanchiin 観智院. Eight of the swordsmiths on this list were from Ōshū schools. Five from Mokusa being Onimaru 鬼丸, Yoyasu 世安, Morifusa 森房, Hatafusa 幡房 and Gaan 瓦安, two from the Tamatsukuri Fuju 諷誦,Houji 寶次 and one from Gassan signing just Gassan 月山. According to the Nihonto Meikan, the Ōshū swordsmith group consists of the Mokusa (舞草), the Gassan (月山) and the Tamatsukuri (玉造), later to become the Hoju (寶壽) schools. Ōshū swords appear in various old books of this time, for example Heiji Monogatari 平治物語 (Tale of Heiji), Konjaku Monogatari 今昔物語 (Anthology of tales from the past), Kojidan 古事談 (Japanese collection of Setsuwa 説話), and Gikeiki 義経記 (War tale that focuses on the legends of Minamoto no Yoshitsune 源義経 and his followers). Ōshū swordsmiths appeared in books in quite early times compared to others. Tales in these books tell of the Emishi-to in the capital city and these swords seem to have been quite popular with the Bushi. Maybe a badge of honour being captured weapons. For example, In “Nihongiryaku” 日本紀略 983AD :” the number of people wearing a funny looking Tachi 太刀 is increasing.” In “Kauyagokau” 高野御幸 1124AD :“ when emperor Shirakawa 白河法皇 visited Kouyasan 高 野山, Fujiwara Zaemon Michisue 藤原左衛門通季 was wearing a Fushū sword “ In “Heihanki” 兵範記 1158AD there was a line that mentioned the Emperor himself had Fushū Tachi.” It seems that during the late Heian the Emishi-to was gaining popularity in Kyoto.

In the middle of the Heian period (794–1185), samurai improved on the Warabitetō to develop Kenukigata-tachi (ja:毛抜形太刀) -early Japanese sword-. To be more precise, it is thought that the Emishi improved the warabitetō and developed Kenukigata-warabitetō (ja:毛抜形蕨手刀) with a hole in the hilt and kenukigatatō (ja:毛抜形刀) without decorations on the tip of the hilt, and the samurai developed kenukigata-tachi based on these swords. Kenukigata-tachi, which was developed in the first half of the 10th century, has a three-dimensional cross-sectional shape of an elongated pentagonal or hexagonal blade called shinogi-zukuri and a gently curved single-edged blade, which are typical features of Japanese swords. There is no wooden hilt attached to kenukigata-tachi, and the tang (nakago) which is integrated with the blade is directly gripped and used. The term kenukigata is derived from the fact that the central part of tang is hollowed out in the shape of an ancient Japanese tweezers (kenuki).

In the tachi developed after kenukigata-tachi, a structure in which the hilt is fixed to the tang (nakago) with a pin called mekugi was adopted. As a result, a sword with three basic external elements of Japanese swords, the cross-sectional shape of shinogi-zukuri, a gently curved single-edged blade, and the structure of nakago, was completed. Its shape may reflects the changing form of warfare in Japan. Cavalry were now the predominant fighting unit and the older straight chokutō were particularly unsuitable for fighting from horseback. The curved sword is a far more efficient weapon when wielded by a warrior on horseback where the curve of the blade adds considerably to the downward force of a cutting action. Early models had uneven curves with the deepest part of the curve at the hilt. As eras changed the center of the curve tended to move up the blade.

The tachi is a sword which is generally larger than a katana, and is worn suspended with the cutting edge down. This was the standard form of carrying the sword for centuries, and would eventually be displaced by the katana style where the blade was worn thrust through the belt, edge up. The tachi was worn slung across the left hip. The signature on the tang of the blade was inscribed in such a way that it would always be on the outside of the sword when worn. This characteristic is important in recognizing the development, function, and different styles of wearing swords from this time onwards.

When worn with full armour, the tachi would be accompanied by a shorter blade in the form known as koshigatana (腰刀, "waist sword"); a type of short sword with no handguard, and where the hilt and scabbard meet to form the style of mounting called an aikuchi ("meeting mouth"). Daggers (tantō), were also carried for close combat fighting as well as carried generally for personal protection.

By the 11th century during the Heian period, Japanese swords had already been exported to neighboring countries in Asia. For example, in the poem "The Song of Japanese Swords" Ouyang Xiu, a statesman of the Song Dynasty in China, described Japanese swords as "It is a treasured sword with a scabbard made of fragrant wood covered with fish skin, decorated with brass and copper, and capable of exorcising evil spirits. It is imported at a great cost.".

From the Heian period (794-1185), ordinary samurai wore swords of the style called kurourusi tachi (kokushitsu no tachi, 黒漆太刀), which meant black lacquer tachi. The hilt of a tachi is wrapped in leather or ray skin, and it is wrapped with black thread or leather cord, and the scabbard is coated with black lacquer. On the other hand, court nobles wore tachi decorated with precisely carved metal and jewels for ceremonial purposes. High-ranking court nobles wore swords of the style called kazari tachi or kaza tachi (飾太刀, 飾剣), which meant decorative tachi, and lower-ranking court nobles wore simplified kazatachi swords of the style called hosodachi (細太刀), which meant thin tachi. The kazatachi and hosodachi worn by nobles were initially straight like a chokutō, but since the Kamakura period they have had a gentle curve under the influence of tachi. Since tachi worn by court nobles were for ceremonial use, they generally had an iron plate instead of a blade.

In the Kamakura period (1185-1333), high-ranking samurai wore hyogo gusari tachi (hyogo kusari no tachi, 兵庫鎖太刀), which meant a sword with chains in the arsenal. The scabbard of the tachi was covered with a gilt copper plate and hung by chains at the waist. At the end of the Kamakura period, simplified hyogo gusari tachi came to be made as an offering to the kami of Shinto shrines and fell out of use as weapons. On the other hand, in the Kamakura period, there was a type of tachi called hirumaki tachi (蛭巻太刀) with a scabbard covered with metal, which was used as a weapon until the Muromachi period. The meaning was a sword wrapped around a leech, and its feature was that a thin metal plate was spirally wrapped around the scabbard, so it was both sturdy and decorative, and chains were not used to hang the scabbard around the waist.

-

Kazari tachi. 12th century, Heian period. National Treasure. Tokyo National Museum.

-

Kurourusi tachi, Shishio. 13th century, Kamakura period. Important Cultural Property. Tokyo National Museum.

-

Hyogo gusari tachi. 13th century, Kamakura period. Important Cultural Property. Tokyo National Museum.

-

Hirumaki tachi. 14th century, Nanboku-chō period. Important Cultural Property. Tokyo National Museum.

The Mongol invasions of Japan in the 13th century during the Kamakura period spurred further evolution of the Japanese sword. The swordsmiths of the Sōshū school represented by Masamune studied tachi that were broken or bent in battle, developed new production methods, and created innovative Japanese swords. They forged the blade using a combination of soft and hard steel to optimize the temperature and timing of the heating and cooling of the blade, resulting in a lighter but more robust blade. They also made the curve of the blade gentle, lengthened the tip linearly, widened the width from the cutting edge to the opposite side of the blade, and thinned the cross section to improve the penetration and cutting ability of the blade.

Historically in Japan, the ideal blade of a Japanese sword has been considered to be the kotō (古刀) (lit., "old swords") in the Kamakura period, and the swordsmiths from the Edo period (1603–1868) to the present day from the shinō (新刀) (lit., "new swords") period focused on reproducing the blade of the Japanese sword made in Kamakura period. There are more than 100 Japanese swords designated as National Treasures in Japan, of which the Kotō of the Kamakura period account for 80% and the tachi account for 70%.

- National treasure tachi from the Kamakura period (Tokyo National Museum)

-

Okadagiri Yoshifusa, by Yoshifusa. Bizen Fukuoka-Ichimonji school. The name comes from the fact that Oda Nobuo killed his vassal Okada with this sword.

-

Nikkō Sukezane, by Sukezane. Fukuoka-Ichimonji school. This sword was owned by Tokugawa Ieyasu.

-

By Sukezane. Bizen Fukuoka-Ichimonji school. This sword was owned by Kishū Tokugawa family.

-

Koryū Kagemitsu, by Kagemitsu. Bizen Osafune school. This sword was owned by Kusunoki Masashige.

From the end of the Kamakura period to the end of the Muromachi period (1333-1573), kawatsutsumi tachi (革包太刀), which means a tachi wrapped in leather, was popular. The kawatsutsumi tachi was stronger than the kurourushi tachi because its hilt was wrapped in leather or ray skin, lacquer was painted on top of it, leather straps and cords were wrapped around it, and the scabbard and sometimes the tsuba (hand guard) were also wrapped in leather.

In the Nanboku-chō period (1336-1392) which corresponds to the early Muromachi period (1336-1573), huge Japanese swords such as ōdachi became popular. The reason for this is thought to be that the conditions for making a practical large-sized sword were established due to the nationwide spread of strong and sharp swords of the Sōshū school. In the case of ōdachi whose blade was 150 cm long, it was impossible to draw a sword from the scabbard on the waist, so people carried it on their back or had their servants carry it. Large naginata and kanabō were also popular in this period.

Katana originates from sasuga, a kind of tantō used by lower-ranking samurai who fought on foot in the Kamakura period. Their main weapon was a long naginata and sasuga was a spare weapon. In the Nanboku-chō period, long weapons such as ōdachi were popular, and along with this, sasuga lengthened and finally became katana. Also, there is a theory that koshigatana (腰刀), a kind of tantō which was equipped by high ranking samurai together with tachi, developed to katana through the same historical background as sasuga, and it is possible that both developed to katana. The oldest katana in existence today is called Hishizukuri uchigatana, which was forged in the Nanbokuchō period, and was dedicated to Kasuga Shrine later.

By the 15th century, Japanese swords had already gained international fame by being exported to China and Korea. For example, Korea learned how to make Japanese swords by sending swordsmiths to Japan and inviting Japanese swordsmiths to Korea. According to the record of June 1, 1430 in the Veritable Records of the Joseon Dynasty, a Korean swordsmith who went to Japan and mastered the method of making Japanese swords presented a Japanese sword to the King of Korea and was rewarded for the excellent work which was no different from the swords made by the Japanese.

Traditionally, yumi (bows) were the main weapon of war in Japan, and tachi and naginata were used only for close combat. The Ōnin War in the late 15th century in the Muromachi period expanded into a large-scale domestic war, in which employed farmers called ashigaru were mobilized in large numbers. They fought on foot using katana shorter than tachi. In the Sengoku period (1467-1615, period of warring states) in the late Muromachi period, the war became bigger and ashigaru fought in a close formation using yari (spears) lent to them. Furthermore, in the late 16th century, tanegashima (muskets) were introduced from Portugal, and Japanese swordsmiths mass-produced improved products, with ashigaru fighting with leased guns. On the battlefield in Japan, guns and spears became main weapons in addition to bows. Due to the changes in fighting styles in these wars, the tachi and naginata became obsolete among samurai, and the katana, which was easy to carry, became the mainstream. The dazzling looking tachi gradually became a symbol of the authority of high-ranking samurai.

On the other hand, kenjutsu (swordsmanship) that makes use of the characteristics of katana was invented. The quicker draw of the sword was well suited to combat where victory depended heavily on short response times. (The practice and martial art for drawing the sword quickly and responding to a sudden attack was called ‘Battōjutsu’, which is still kept alive through the teaching of Iaido.) The katana further facilitated this by being worn thrust through a belt-like sash (obi) with the sharpened edge facing up. Ideally, samurai could draw the sword and strike the enemy in a single motion. Previously, the curved tachi had been worn with the edge of the blade facing down and suspended from a belt.

From the 15th century, low-quality swords were mass-produced under the influence of the large-scale war. These swords, along with spears, were lent to recruited farmers called ashigaru and swords ware exported . Such mass-produced swords are called kazuuchimono, and swordsmiths of the Bisen school and Mino school produced them by division of labor. The export of Japanese sword reached its height during the Muromachi period when at least 200,000 swords were shipped to Ming Dynasty China in official trade in an attempt to soak up the production of Japanese weapons and make it harder for pirates in the area to arm. In the Ming Dynasty of China, Japanese swords and their tactics were studied to repel pirates, and wodao and miaodao were developed based on Japanese swords.

From this period, the tang (nakago) of many old tachi were cut and shortened into katana. This kind of remake is called suriage (磨上げ). For example, many of the tachi that Masamune forged during the Kamakura period were converted into katana, so his only existing works are katana and tantō. During this period, a great flood occurred in Bizen, which was the largest production area of Japanese swords, and the Bizen school rapidly declined, after which the Mino school flourished.

From around the 16th century, many Japanese swords were exported to Thailand, where katana-style swords were made and prized for battle and art work, and some of them are in the collections of the Thai royal family.

In the Sengoku period (1467-1615) or the Azuchi–Momoyama period (1568-1600), the itomaki tachi (itomaki no tachi, 糸巻太刀), which means a tachi wound with thread, appeared and became the mainstream of tachi after that. itomaki tachi was decorated with gorgeous lacquer decorations with lots of maki-e and flashy colored threads, and was used as a gift, a ceremony, or an offering to the kami of Shinto shrines.

In later Japanese feudal history, during the Sengoku and Edo periods, certain high-ranking warriors of what became the ruling class would wear their sword tachi-style (edge-downward), rather than with the scabbard thrust through the belt with the edge upward. This style of swords is called handachi, "half tachi". In handachi, both styles were often mixed, for example, fastening to the obi was katana style, but metalworking of the scabbard was tachi style.

In the Muromachi period, especially the Sengoku period, anybody such as farmers, townspeople and monks could equip a sword. However, in 1588 during the Azuchi–Momoyama period, Toyotomi Hideyoshi conducted a sword hunt and banned farmers from owning them with weapons.

However, Toyotomi's sword hunt couldn't disarm peasants. Farmers and townspeople could wear daisho until 1683. And most of them kept wearing wakizashi on a daily basis until the middle of the 18th century. After then they wore it special times(travel, wedding, funeral) until meiji restoration.

Shintō – Shinshintō (New swords)

Swords forged after 1596 in the Keichō period of the Azuchi-Momoyama period are classified as shintō (New swords). Japanese swords since shintō are different from kotō in forging method and steel (tamahagane). This is thought to be because Bizen school, which was the largest swordsmith group of Japanese swords, was destroyed by a great flood in 1590 and the mainstream shifted to Mino school, and because Toyotomi Hideyoshi virtually unified Japan, uniform steel began to be distributed throughout Japan. The kotō swords, especially the Bizen school swords made in the Kamakura period, had a midare-utsuri like a white mist between hamon and shinogi, but the swords since shinto have almost disappeared. In addition, the whole body of the blade became whitish and hard. Almost no one was able to reproduce midare-utsurii until Kunihira Kawachi reproduced it in 2014.

Japanese swords since the sintō period often have gorgeous decorations carved on the blade and lacquered maki-e decorations on the scabbard. This was due to the economic development and the increased value of swords as arts and crafts as the Sengoku Period ended and the peaceful Edo Period began. The Umetada school led by Umetada Myoju who was considered to be the founder of shinto led the improvement of the artistry of Japanese swords in this period. They were both swordsmiths and metalsmiths, and were famous for carving the blade, making metal accouterments such as tsuba (handguard), remodeling from tachi to katana (suriage), and inscriptions inlaid with gold.

During this period, the Tokugawa shogunate required samurai to wear Katana and shorter swords in pairs. These short swords were wakizashi and tantō, and wakizashi were mainly selected. This set of two is called a daishō. Only samurai could wear the daishō: it represented their social power and personal honour. Samurai could wear decorative sword mountings in their daily lives, but the Tokugawa shogunate regulated the formal sword that samurai wore when visiting a castle by regulating it as a daisho made of a black scabbard, a hilt wrapped with white ray skin and black string.

Townspeople (Chōnin) and farmers were allowed to equip a short wakizashi, and the public were often equipped with wakizashi on their travels. Under the Tokugawa shogunate, swordmaking and the use of firearms declined. Japanese swords made in this period is classified as shintō.

In the late 18th century, swordsmith Suishinshi Masahide criticized that the present katana blades only emphasized decoration and had a problem with their toughness. He insisted that the bold and strong kotō blade from the Kamakura period to the Nanboku-chō period was the ideal Japanese sword, and started a movement to restore the production method and apply it to katana. Katana made after this is classified as a shinshintō (新々刀), "new revival swords" or literally "new-new swords." One of the most popular swordsmiths in Japan today is Minamoto Kiyomaro who was active in this shinshintō period. His popularity is due to his timeless exceptional skill, as he was nicknamed "Masamune in Yotsuya" and his disastrous life. His works were traded at high prices and exhibitions were held at museums all over Japan from 2013 to 2014.

The arrival of Matthew Perry in 1853 and the subsequent Convention of Kanagawa caused chaos in Japanese society. Conflicts began to occur frequently between the forces of sonnō jōi (尊王攘夷派), who wanted to overthrow the Tokugawa Shogunate and rule by the Emperor, and the forces of sabaku (佐幕派), who wanted the Tokugawa Shogunate to continue. These political activists, called the shishi (志士), fought using a practical katana, called the kinnōtō (勤皇刀) or the bakumatsutō (幕末刀). Their katana were often longer than 90 cm (35.43 in) in blade length, less curved, and had a big and sharp point, which was advantageous for stabbing in indoor battles.

Gendaitō (Modern or contemporary swords)

In 1867, the Tokugawa Shogunate declared the return of Japan's sovereignty to the Emperor, and from 1868, the government by the Emperor and rapid modernization of Japan began, which was called the Meiji Restoration. The Haitōrei Edict in 1876 all but banned carrying swords and guns on streets. Overnight, the market for swords died, many swordsmiths were left without a trade to pursue, and valuable skills were lost. Swords forged after the Haitōrei Edict are classified as gendaitō. The craft of making swords was kept alive through the efforts of some individuals, notably Miyamoto kanenori (宮本包則, 1830–1926) and Gassan Sadakazu (月山貞一, 1836–1918), who were appointed Imperial Household Artist. These smiths produced fine works that stand with the best of the older blades for the Emperor and other high-ranking officials. The businessman Mitsumura Toshimo (光村利藻, 1877-1955)tried to preserve their skills by ordering swords and sword mountings from the swordsmiths and craftsmen. He was especially enthusiastic about collecting sword mountings, and he collected about 3,000 precious sword mountings from the end of the Edo period to the Meiji period. About 1200 items from a part of the collection are now in the Nezu Museum.

The Japanese sword remained in use in some occupations such as the police force. At the same time, kendo was incorporated into police training so that police officers would have at least the training necessary to properly use one. In time, it was rediscovered that soldiers needed to be armed with swords, and over the decades at the beginning of the 20th century swordsmiths again found work. These swords, derisively called guntō, were often oil-tempered, or simply stamped out of steel and given a serial number rather than a chiseled signature. The mass-produced ones often look like Western cavalry sabers rather than Japanese swords, with blades slightly shorter than blades of the shintō and shinshintō periods. In 1934 the Japanese government issued a military specification for the shin guntō (new army sword), the first version of which was the Type 94 Katana, and many machine- and hand-crafted swords used in World War II conformed to this and later shin guntō specifications.

- Military Swords of Imperial Japan (Guntō)

-

kyu guntō army sabre

-

"Type 98" officer's sword

-

"Type 95" Non Commissioned Officer's sword of World War II; made to resemble a Commissioned Officer's shin guntō.

-

World War II Japanese naval officers sword kai gunto.

Under the United States occupation at the end of World War II all armed forces in occupied Japan were disbanded and production of Japanese swords with edges was banned except under police or government permit. The ban was overturned through a personal appeal by Dr. Junji Honma. During a meeting with General Douglas MacArthur, Honma produced blades from the various periods of Japanese history and MacArthur was able to identify very quickly what blades held artistic merit and which could be considered purely weapons. As a result of this meeting, the ban was amended so that guntō weapons would be destroyed while swords of artistic merit could be owned and preserved. Even so, many Japanese swords were sold to American soldiers at a bargain price; in 1958 there were more Japanese swords in America than in Japan. The vast majority of these one million or more swords were guntō, but there were still a sizable number of older swords.

After the Edo period, swordsmiths turned increasingly to the production of civilian goods. The Occupation and its regulations almost put an end to the production of Japanese swords. A few smiths continued their trade, and Honma went on to be a founder of the Society for the Preservation of the Japanese Sword (日本美術刀剣保存協会, Nippon Bijutsu Tōken Hozon Kyōkai), who made it their mission to preserve the old techniques and blades. Thanks to the efforts of other like-minded individuals, the Japanese swords did not disappear, many swordsmiths continued the work begun by Masahide, and the old swordmaking techniques were rediscovered.

Nowadays, iaitō is used for iaidō. Due to their popularity in modern media, display-only Japanese swords have become widespread in the sword marketplace. Ranging from small letter openers to scale replica "wallhangers", these items are commonly made from stainless steel (which makes them either brittle (if made from cutlery-grade 400-series stainless steel) or poor at holding an edge (if made from 300-series stainless steel)) and have either a blunt or very crude edge. There are accounts of good quality stainless steel Japanese swords, however, these are rare at best. Some replica Japanese swords have been used in modern-day armed robberies. As a part of marketing, modern ahistoric blade styles and material properties are often stated as traditional and genuine, promulgating disinformation. Some companies and independent smiths outside Japan produce katana as well, with varying levels of quality. According to the Parliamentary Association for the Preservation and Promotion of Japanese Swords, organized by Japanese Diet members, many Japanese swords distributed around the world as of the 21st century are fake Japanese-style swords made in China. The Sankei Shimbun analyzed that this is because the Japanese government allowed swordsmiths to make only 24 Japanese swords per person per year in order to maintain the quality of Japanese swords.

In Japan, genuine edged hand-made Japanese swords, whether antique or modern, are classified as art objects (and not weapons) and must have accompanying certification in order to be legally owned. Prior to WWII Japan had 1.5million swords in the country – 200,000 of which had been manufactured in factories during the Meiji Restoration. As of 2008, only 100,000 swords remain in Japan. It is estimated that 250,000–350,000 sword have been brought to other nations as souvenirs, art pieces or for Museum purposes. 70% of daito (long swords), formerly owned by Japanese officers, have been exported or brought to the United States.

Many swordsmiths since the Edo period have tried to reproduce the sword of the Kamakura period which is considered as the best sword in the history of Japanese swords, but they have failed. Then, in 2014, Kunihira Kawachi succeeded in reproducing it and won the Masamune Prize, the highest honor as a swordsmith. No one could win the Masamune Prize unless he made an extraordinary achievement, and in the section of tachi and katana, no one had won for 18 years before Kawauchi.

The popularity of Japanese swords among Japanese women increased dramatically after the release of a browser video game called Touken Ranbu, featuring anthropomorphic characters of famous Japanese swords, in 2015. Since then, sales of books on Japanese swords have increased dramatically, and the number of special exhibitions at various museums featuring famous historical swords has increased dramatically, leading to a dramatic increase in the number of visitors to museums. In addition, museums and Shinto shrines have launched a number of crowdfunding programmes to purchase historical swords featured in games from private owners, as well as reproductions of swords and new sword mountings, increasing the number of opportunities to view these masterpieces. With the increased interest in Japanese swords, gendaitō swordsmiths are now being asked by women for their autographs.

Cultural and social significance

The events of Japanese society have shaped the craft of sword making, as has the sword itself influenced the course of cultural and social development within the nation.

The Museum of Fine Arts states that when an artisan plunged the newly crafted sword into the cold water, a portion of his spirit was transferred into the sword. His spirit, morals and state of mind at the time became crucial to the defining of the swords moral and physical characteristics

During the Jōmon Period (10,000-1000BCE) swords resembled iron knife blades and were used for hunting, fishing and farming. There is the idea that swords were more than a tool during the Jōmon period, no swords have been recovered to back this hypothesis.

The Yayoi Period (1000BCE-300CE) saw the establishment of villages and the cultivation of rice farming within Japan. Rice farming came as a result of Chinese and Korean influence, they were the first group of people to introduce swords into the Japanese Isles. Subsequently, bronze swords were used for religious ceremonies. The Yayoi period saw swords be used primarily for religious and ceremonial purposes.

During the Kofun Period (250-538CE) Animism was introduced into Japanese society. Animism is the belief that everything in life contains or is connected to a divine spirits. This connection to the spirit world premediates the introduction of Buddhism into Japan. During this time, China was craving steel blades on the Korean Peninsula. Japan saw this as a threat to national security and felt the need to develop their military technology. As a result, clan leaders took power as military elites, fighting one another for power and territory. As dominant figures took power, loyalty and servitude became an important part of Japanese life – this became the catalyst for the honour culture that is often affiliated with Japanese people.

In the Edo period (1603–1868), swords gained prominence in everyday life as the “most important” part of a warrior's amour. The Edo era saw swords became a mechanism for bonding between Daimyo and Samurai. Daimyo would gift samurai's with swords as a token of their appreciation for their services. In turn, samurai would gift Daimyo swords as a sign of respect, most Daimyo would keep these swords as family heirlooms. In this period, it was believed that swords were multifunctional; in spirit they represent proof of military accomplishment, in practice they are coveted weapons of war and diplomatic gifts.

The peace of the Edo period saw the demand for swords fall. To retaliate, in 1719 the eighth Tokugawa shogun, Yoshimune, compiled a list of “most famous swords”. Masamune, Awatacuchi Yoshimitsu, and Go no Yoshihiro were dubbed the “Three Famous Smiths”, their swords became sought after by the Daimyo. The prestige and demand for these status symbols spiked the price for these fine pieces.

During the Late-Edo period, Suishinshi Masahide wrote that swords should be less extravagant. Swords began to be simplified and altered to be durable, sturdy and made to cut well. In 1543 guns arrived in Japan, changing military dynamic and practicality of swords and samurai's. This period also saw introduction of martial arts as a means to connecting to the spirit world and allowed common people to participate in samurai culture.

The Meiji Period (1868–1912) saw the dissolution of the samurai class, after foreign powers demanded Japan open their borders to international trade – 300-hundred years of Japanese isolation came to an end. In 1869 and 1873, two petition were submitted to government to abolish the custom of sword wearing because people feared the outside world would view swords as a “tool for bloodshed” and would consequentially associate Japanese people as violent. Haitōrei (1876) outlawed and prohibited wearing swords in public, with the exception for those in the military and government official; swords lost their meaning within society. Emperor Meiji was determined to westernize Japan with the influence of American technological and scientific advances; however, he himself appreciated the art of sword making. The Meiji era marked the final moments of samurai culture, as samurai's were no match for conscript soldiers who were trained to use western firearms. Some samurai found it difficult to assimilate to the new culture as they were forced to give up their privileges, while others preferred this less-hierarchical way of life. Even with the ban, the Sino-Japanese War (1894) saw Japanese troops wear swords into battle, not for practical use but for symbolic reasons.

The Meiji era also saw the integration of Buddhism into Shinto Japanese beliefs. Swords were no longer necessary, in war or lifestyle, and those who practiced martial arts became the “modern samurai” – young children were still groomed to serve the emperor and put loyalty and honour above all else, as this new era of rapid development required loyal, hard working men. The practice of sword making was prohibited, thus swords during the Meiji period were obsolete and a mere symbol of status. Swords were left to rust, sold or melted into more ‘practical’ objects for everyday life.

Prior to and during WWII, even with the modernization of the army, the demand for swords exceeded the number of swordsmiths still capable of making them. As a result, swords of this era are of poor quality. In 1933, during the Shōwa era (1926–1989), a sword making factory designed to re-establish the “spirit of Japan” through the art of sword making was built to preserve the legacy and art of swordsmiths and sword making. The government at the time feared that the warrior spirit (loyalty and honour) was disappearing within Japan, along with the integrity and quality of swords.

For a portion of the US occupation of Japan, sword making, swordsmiths and wielding of swords was prohibited. As a means to preserve the warrior culture of Japan, martial arts was put into the school curriculum. In 1953, America finally lifted the ban on swords after realizing that sword making is an important cultural asset to preserving Japanese history and legacy.

Religion, honour and mythology

The origins of Japanese swords and their effects and influence on society differs depending on the story that is followed.

- Swords and warriors are closely associated with Shinto in Japanese culture. Shinto is “the way of the gods”, meaning that all elements of the world are embedded with god like spirits. Shinto endorses self-purification, ancestral worship, nature-worship and imperial divinity. It is said that swords are a source of wisdom and “emanate energy” to inspire the wielder. As Shintoism shaped the progress of Japanese expansionism and international affairs so too did the sword become a mechanism for change.

- There is a Japanese legend that, along with the mirror and the jewels, the sword makes up one of three Imperial Icons. The Imperial Icons present the three values and personality traits that all good emperors should possess as leaders of celestial authority.

- Japanese mythology states that the sword is a “symbol of truth” and a “token of virtue”. Legend states originate from the battle between Amaterasu and her brother, Susa-no-wo-o-no Mikotot (Susa-no). In order to defeat Susa-no, Amaterasu split the ten-span sword until she broke herself into three pieces. Legend states that the sword can “create union by imposing social order” because it hold the ability to cut objects into two or more pieces and dictate the shape and size of the pieces.

- Mythology also suggests that when Emperor Jimmu Tennō was moving his army through the land, a deity blocked their path with toxic gas which caused them to drift into an indefinite slumber. Upon seeing this, Amaterasu pleaded with the God of Thunder to punish the deity and allow the emperor to proceed. The God of Thunder, instead of following her orders, sent his sword down to the emperor to subdue the land. Upon receiving the sword, the emperor woke up, along with his troops and they proceeded with their mission. According this legend, swords have the power to save the imperial (divine) bloodline in times of need.

- In martial arts training, it is believed that within a sword:

- "The blade represents the juncture where the wisdom of leaders and gods intersects with the commoner. The sword represents the implement by which societies are managed. The effectiveness of the sword as a tool and the societal beliefs surrounding it both lift the sword to the pinnacle of warrior symbolism."

- Swords are a symbol of Japanese honour and esteem for hand-to-hand combat. They represent the idea that taking another's life should be done with honour, and long-range combat (firearms) is a cowardly way to end another's life. This also connects to the Japanese belief of self-sacrifice, warriors should be ready to lay down their lives for their nation (emperor).

There is a rich relationship between swords, Japanese culture, and societal development. The different interpretations of the origins of swords and their connection to the spirit world, each hold their own merit within Japanese society, past and present. Which one and how modern-day samurai interpret the history of swords, help influence the kind of samurai and warrior they choose to be.

Manufacturing

Japanese swords are generally made by a division of labor between six and eight craftsmen. Tosho (Toko, Katanakaji) is in charge of forging blades, togishi is in charge of polishing blades, kinkosi (chokinshi) is in charge of making metal fittings for sword fittings, shiroganeshi is in charge of making habaki (blade collar), sayashi is in charge of making scabbards, nurishi is in charge of applying lacquer to scabbards, tsukamakishi is in charge of making hilt, and tsubashi is in charge of making tsuba (hand guard). Tosho use apprentice swordsmiths as assistants. Prior to the Muromachi period, tosho and kacchushi (armorer) used surplus metal to make tsuba, but from the Muromachi period onwards, specialized craftsmen began to make tsuba. Nowadays, kinkoshi sometimes serves as shiroganeshi and tsubashi.

Typical features of Japanese swords represented by katana and tachi are a three-dimensional cross-sectional shape of an elongated pentagonal or hexagonal blade called shinogi-zukuri, a style in which the blade and the tang (nakago) are integrated and fixed to the hilt (tsuka) with a pin called mekugi, and a gentle curve. When a shinogi-zukuri sword is viewed from the side, there is a ridge line of the thickest part of the blade called shinogi between the cutting edge side and the back side. This shinogi contributes to lightening and toughening of the blade and high cutting ability.

Japanese swords were often forged with different profiles, different blade thicknesses, and varying amounts of grind. Wakizashi and tantō, for instance, were not simply scaled-down versions of katana; they were often forged in a shape called hira-zukuri, in which the cross-sectional shape of the blade becomes an isosceles triangle.

The daishō was not always forged together. If a samurai was able to afford a daishō, it was often composed of whichever two swords could be conveniently acquired, sometimes by different smiths and in different styles. Even when a daishō contained a pair of blades by the same smith, they were not always forged as a pair or mounted as one. Daishō made as a pair, mounted as a pair, and owned/worn as a pair, are therefore uncommon and considered highly valuable, especially if they still retain their original mountings (as opposed to later mountings, even if the later mounts are made as a pair).

The forging of a Japanese blade typically took weeks or even months and was considered a sacred art. As with many complex endeavors, rather than a single craftsman, several artists were involved. There was a smith to forge the rough shape, often a second smith (apprentice) to fold the metal, a specialist polisher (called a togi) as well as the various artisans that made the koshirae (the various fittings used to decorate the finished blade and saya (sheath) including the tsuka (hilt), fuchi (collar), kashira (pommel), and tsuba (hand guard)). It is said that the sharpening and polishing process takes just as long as the forging of the blade itself.

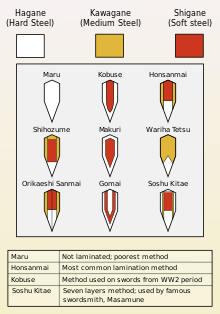

The legitimate Japanese sword is made from Japanese steel "Tamahagane". The most common lamination method the Japanese sword blade is formed from is a combination of two different steels: a harder outer jacket of steel wrapped around a softer inner core of steel. This creates a blade which has a hard, razor sharp cutting edge with the ability to absorb shock in a way which reduces the possibility of the blade breaking when used in combat. The hadagane, for the outer skin of the blade, is produced by heating a block of raw steel, which is then hammered out into a bar, and the flexible back portion. This is then cooled and broken up into smaller blocks which are checked for further impurities and then reassembled and reforged. During this process the billet of steel is heated and hammered, split and folded back upon itself many times and re-welded to create a complex structure of many thousands of layers. Each different steel is folded differently, in order to provide the necessary strength and flexibility to the different steels. The precise way in which the steel is folded, hammered and re-welded determines the distinctive grain pattern of the blade, the jihada, (also called jigane when referring to the actual surface of the steel blade) a feature which is indicative of the period, place of manufacture and actual maker of the blade. The practice of folding also ensures a somewhat more homogeneous product, with the carbon in the steel being evenly distributed and the steel having no voids that could lead to fractures and failure of the blade in combat.

The shingane (for the inner core of the blade) is of a relatively softer steel with a lower carbon content than the hadagane. For this, the block is again hammered, folded and welded in a similar fashion to the hadagane, but with fewer folds. At this point, the hadagane block is once again heated, hammered out and folded into a ‘U’ shape, into which the shingane is inserted to a point just short of the tip. The new composite steel billet is then heated and hammered out ensuring that no air or dirt is trapped between the two layers of steel. The bar increases in length during this process until it approximates the final size and shape of the finished sword blade. A triangular section is cut off from the tip of the bar and shaped to create what will be the kissaki. At this point in the process, the blank for the blade is of rectangular section. This rough shape is referred to as a sunobe.

The sunobe is again heated, section by section and hammered to create a shape which has many of the recognisable characteristics of the finished blade. These are a thick back (mune), a thinner edge (ha), a curved tip (kissaki), notches on the edge (hamachi) and back (munemachi) which separate the blade from the tang (nakago). Details such as the ridge line (shinogi) another distinctive characteristic of the Japanese sword, are added at this stage of the process. The smith's skill at this point comes into play as the hammering process causes the blade to naturally curve in an erratic way, the thicker back tending to curve towards the thinner edge, and he must skillfully control the shape to give it the required upward curvature. The sunobe is finished by a process of filing and scraping which leaves all the physical characteristics and shapes of the blade recognisable. The surface of the blade is left in a relatively rough state, ready for the hardening processes. The sunobe is then covered all over with a clay mixture which is applied more thickly along the back and sides of the blade than along the edge. The blade is left to dry while the smith prepares the forge for the final heat treatment of the blade, the yaki-ire, the hardening of the cutting edge.

This process takes place in a darkened smithy, traditionally at night, in order that the smith can judge by eye the colour and therefore the temperature of the sword as it is repeatedly passed through the glowing charcoal. When the time is deemed right (traditionally the blade should be the colour of the moon in February and August which are the two months that appear most commonly on dated inscriptions on the tang), the blade is plunged edge down and point forward into a tank of water. The precise time taken to heat the sword, the temperature of the blade and of the water into which it is plunged are all individual to each smith and they have generally been closely guarded secrets. Legend tells of a particular smith who cut off his apprentice's hand for testing the temperature of the water he used for the hardening process. In the different schools of swordmakers there are many subtle variations in the materials used in the various processes and techniques outlined above, specifically in the form of clay applied to the blade prior to the yaki-ire, but all follow the same general procedures.

The application of the clay in different thicknesses to the blade allows the steel to cool more quickly along the thinner coated edge when plunged into the tank of water and thereby develop into the harder form of steel called martensite, which can be ground to razor-like sharpness. The thickly coated back cools more slowly retaining the pearlite steel characteristics of relative softness and flexibility. The precise way in which the clay is applied, and partially scraped off at the edge, is a determining factor in the formation of the shape and features of the crystalline structure known as the hamon. This distinctive tempering line found near the edge is one of the main characteristics to be assessed when examining a blade.

The martensitic steel which forms from the edge of the blade to the hamon is in effect the transition line between these two different forms of steel, and is where most of the shapes, colours and beauty in the steel of the Japanese sword are to be found. The variations in the form and structure of the hamon are all indicative of the period, smith, school or place of manufacture of the sword. As well as the aesthetic qualities of the hamon, there are, perhaps not unsurprisingly, real practical functions. The hardened edge is where most of any potential damage to the blade will occur in battle. This hardened edge is capable of being reground and sharpened many times, although the process will alter the shape of the blade. Altering the shape will allow more resistance when fighting in hand-to-hand combat.

Almost all blades are decorated, although not all blades are decorated on the visible part of the blade. Once the blade is cool, and the mud is scraped off, grooves and markings (hi or bo-hi) may be cut into it. One of the most important markings on the sword is performed here: the file markings. These are cut into the tang or the hilt-section of the blade, where they will be covered by the hilt later. The tang is never supposed to be cleaned; doing this can reduce the value of the sword by half or more. The purpose is to show how well the steel ages.

Some other marks on the blade are aesthetic: dedications written in Kanji characters as well as engravings called horimono depicting gods, dragons, or other acceptable beings. Some are more practical. The presence of a groove (the most basic type is called a hi) reduces the weight of the sword yet keeps its structural integrity and strength.

Use

The tachi became the primary weapon on the battlefield during the Kamakura period, used by cavalry. The sword was mostly considered as a secondary weapon until then, used in the battlefield only after the bow and polearm were no longer feasible. During the Edo period samurai went about on foot unarmored, and with much less combat being fought on horseback in open battlefields the need for an effective close quarter weapon resulted in samurai being armed with daishō.

Testing of swords, called tameshigiri, was practiced on a variety of materials (often the bodies of executed criminals) to test the sword's sharpness and practice cutting techniques.

Kenjutsu is the Japanese martial art of using the Japanese swords in combat. The Japanese swords are primarily a cutting weapon, or more specifically, a slicing one. Its moderate curve, however, allowed for effective thrusting as well. The hilt was held with two hands, though a fair amount of one-handed techniques exist. The placement of the right hand was dictated by both the length of the handle and the length of the wielder's arm. Two other martial arts were developed specifically for training to draw the sword and attack in one motion. They are battōjutsu and iaijutsu, which are superficially similar, but do generally differ in training theory and methods.

For cutting, there was a specific technique called "ten-uchi." Ten-uchi refers to an organized motion made by arms and wrist, during a descending strike. As the sword is swung downwards, the elbow joint drastically extends at the last instant, popping the sword into place. This motion causes the swordsman's grip to twist slightly and if done correctly, is said to feel like wringing a towel (Thomas Hooper reference). This motion itself caused the sword's blade to impact its target with sharp force, and is used to break initial resistance. From there, fluidly continuing along the motion wrought by ten-uchi, the arms would follow through with the stroke, dragging the sword through its target. Because the Japanese swords slices rather than chops, it is this "dragging" which allows it to do maximum damage, and is thus incorporated into the cutting technique. At full speed, the swing will appear to be full stroke, the sword passing through the targeted object. The segments of the swing are hardly visible, if at all. Assuming that the target is, for example, a human torso, ten-uchi will break the initial resistance supplied by shoulder muscles and the clavicle. The follow through would continue the slicing motion, through whatever else it would encounter, until the blade inherently exited the body, due to a combination of the motion and its curved shape.

Nearly all styles of kenjutsu share the same five basic guard postures. They are as follows; chūdan-no-kamae (middle posture), jōdan-no-kamae (high posture), gedan-no-kamae (low posture), hassō-no-kamae (eight-sided posture), and waki-gamae (side posture).