32P/Comas Solà

In this article, we will explore the fascinating world of 32P/Comas Solà, which has captured the attention of experts and enthusiasts alike. From its impact on contemporary society to its historical roots, 32P/Comas Solà has been the subject of intense debate and analysis. Throughout these pages, we will examine the different aspects of 32P/Comas Solà, from its influence on popular culture to its relevance in academia. Through this journey, we hope to offer a complete and nuanced view of 32P/Comas Solà, giving our readers a deeper understanding of this fascinating topic.

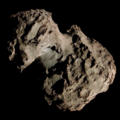

Infrared image of Comet Comas Solà taken by NEOWISE on 4 December 2014 | |

| Discovery[1] | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by | Josep Comas i Solà |

| Discovery site | Fabra Observatory |

| Discovery date | 4 November 1926 |

| Designations | |

| P/1926 V1, P/1935 P1 | |

| |

| Orbital characteristics[3][4] | |

| Epoch | 5 May 2025 (JD 2460800.5) |

| Observation arc | 98.49 years |

| Number of observations | 5,507 |

| Aphelion | 7.082 AU |

| Perihelion | 2.025 AU |

| Semi-major axis | 4.554 AU |

| Eccentricity | 0.55529 |

| Orbital period | 9.718 years |

| Inclination | 9.920° |

| 54.532° | |

| Argument of periapsis | 54.703° |

| Mean anomaly | 38.473° |

| Last perihelion | 20 April 2024 |

| Next perihelion | 15 January 2034[2] |

| TJupiter | 2.678 |

| Earth MOID | 1.029 AU |

| Jupiter MOID | 0.247 AU |

| Physical characteristics[3] | |

Mean radius | 2.52 km (1.57 mi)[5] |

| 7.3 hours[6] | |

| Comet total magnitude (M1) | 10.3 |

| Comet nuclear magnitude (M2) | 13.5 |

32P/Comas Solà is a periodic comet with a current orbital period of 9.7 years around the Sun. It is the second of two comets discovered by Spanish astronomer, Josep Comas Solà.[a]

Observational history

The comet was discovered on 4 November 1926, by Josep Comas Solà. As part of his work on asteroids for the Fabra Observatory (Barcelona), he was taking photographs with a 6-inch (150 mm) telescope. At the time, its position was located within the constellation Cetus.[b] The comet's past orbital evolution became a point of interest as several astronomers suggested early on that the comet might be a return of the then lost periodic comet 113P/Spitaler. In 1935, additional positions had been obtained, and P. Ramensky investigated the orbital motion back to 1911. He noted the comet passed very close to Jupiter during May 1912 and that, prior to this approach, the comet had a perihelion distance of 2.15 AU (322 million km) and an orbital period of 9.43 years. The identity with Comet Spitaler was thus disproven.

In 1933, the Danish astronomer Julie Vinter Hansen undertook significant new research which calculated the orbit of the comet up to 1980, predicting when it would return to the Earth's orbit.[7]

While searching for 32P/Comas Solà in 1969, two Soviet astronomers Klim Churyumov and Svetlana Gerasimenko accidentally discovered a new comet in photographic plates they took, which is now known as 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko.[8]

Physical characteristics

Nucleus size

In 1985, precession models of the comet's nucleus derived an equatorial radius somewhere between 0.99–1.15 km (0.62–0.71 mi).[9] CCD photometry of the comet taken while it was 3.1 AU (460 million km) from the Sun in 1999 obtained a larger upper limit about 3.2 km (2.0 mi).[10] Further studies in 2006 revised the size estimate to be about 2.52 km (1.57 mi).[5]

Rotation period

Initial estimates of the rotation period indicated that the comet spins around its axis once every 1.5 to 2.3 days.[9] However, based on the 1999 estimate of the size of its nucleus, forced precession models obtained in 2001 indicated a shorter rotation period of around 7.3 hours.[6]

Notes

- ^ Josep Comas Solà independently co-discovered C/1925 F1 (Shajn–Comas Solá) over a year earlier with Grigory Shajn.

- ^ Reported initial position upon discovery was: α = 2h 56m 36s, δ = –6° 31′[1]

References

- ^ a b J. Comas Solà (6 November 1926). E. Strömgren (ed.). "A New Comet". IAU Circular. 122 (1).

- ^ "Horizons Batch for 32P/Comas Sola (90000431) on 2034-Jan-15" (Perihelion occurs when rdot flips from negative to positive). JPL Horizons. Retrieved 26 September 2025. (JPL#K242/47 Soln.date: 2025-Jul-07)

- ^ a b "32P/Comas Solà – JPL Small-Body Database Lookup". ssd.jpl.nasa.gov. Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Retrieved 26 February 2010.

- ^ "32P/Comas Solà Orbit". Minor Planet Center. Retrieved 29 October 2014.

- ^ a b G. Tancredi; J. A. Fernández; H. Rickman; J. Licandro (2006). "Nuclear magnitudes and the size distribution of Jupiter family comets". Icarus. 182 (2): 527–549. Bibcode:2006Icar..182..527T. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2006.01.007.

- ^ a b M. Królikowska; G. Sitarski; S. Szutowicz (2001). "Forced precession models for six erratic comets" (PDF). Astronomy & Astrophysics. 368 (2): 676–688. Bibcode:2001A&A...368..676K. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20000541.

- ^ J. M. Vinter Hansen (1933). "The periodic comet Comas Sola (1926 f) at its return in the year 1935". Publikationer og Mindre Meddeler Fra Kobenhavns Observatorium. 85: 1–16. Bibcode:1933PCopO..85....1H.

- ^ G. W. Kronk; M. Meyer (2010). Cometography: A Catalog of Comets. Vol. 5: 1960–1982. Cambridge University Press. pp. 241–245. ISBN 978-0-521-87226-3.

- ^ a b Z. Sekanina (1985). "Nucleus precession of periodic comet Comas Solà". The Astronomical Journal. 90: 1370–1381. Bibcode:1985AJ.....90.1370S. doi:10.1086/113844. ISSN 0004-6256.

- ^ S. C. Lowry; A. Fitzsimmons; I. M. Cartwright; I. P. Williams (1999). "CCD photometry of distant comets". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 349: 649–659. Bibcode:1999A&A...349..649L.

External links

- 32P/Comas Solà at the JPL Small-Body Database

- 32P/Comas Solà at Seiichi Yoshida's website

- 32P/Comas Solà at Gary W. Kronk's Cometography