Circle packing theorem

In today's world, Circle packing theorem has become a relevant and interesting topic for a wide spectrum of people. Whether it is a public figure, a concept, or a historical event, Circle packing theorem sparks the interest and curiosity of many. Throughout history, Circle packing theorem has played a crucial role in forming societies and shaping culture and traditions. In this article, we will explore the meaning and importance of Circle packing theorem in depth, offering a detailed and insightful look that will shed light on this fascinating topic.

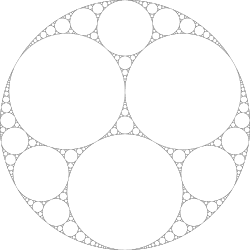

The circle packing theorem (also known as the Koebe–Andreev–Thurston theorem) describes the possible patterns of tangent circles among non-overlapping circles in the plane. A circle packing is a collection of circles whose union is connected and whose interiors are disjoint. The intersection graph of a circle packing, called a coin graph,[1] is the graph having a vertex for each circle, and an edge for every pair of circles that are tangent. Coin graphs are always connected, simple, and planar. The circle packing theorem states that these are the only requirements for a graph to be a coin graph: every finite connected simple planar graph has a circle packing in the plane whose intersection graph is isomorphic to .

A stronger form of the circle packing theorem applies to any polyhedral graph and its dual graph, and proves the existence of a primal-dual packing, circle packings for both graphs that cross at right angles. Circle packings and their tangencies, and the circle packing theorem, have been extended to arbitrary Riemannian surfaces including the sphere, the hyperbolic plane, and to surfaces of bounded genus. More generally, intersection graphs of interior-disjoint geometric objects are called tangency graphs[2] or contact graphs.[3]

Circle packings have applications in conformal mapping, the construction of polyhedra, planar separator theorems, graph drawing, and the theory of random walks. The study of the tangencies of circle packings, for which the circle packing theorem is central, should be distinguished from the study of circle packings within fixed shapes but without specified tangencies, typically studied with respect to their density (the fraction of area covered by circles).

Existence and uniqueness

Theorem statement

A maximal planar graph is a finite simple planar graph to which no more edges can be added while preserving planarity. It may be embedded in the plane with different choices of the outer face, but all such embeddings share the same set of faces (including the outer face) which must all be triangles. The circle packing theorem guarantees the existence of a circle packing with finitely many circles whose intersection graph is isomorphic to . As the following theorem states more formally, every maximal planar graph can have at most one packing.[4]

Koebe–Andreev–Thurston circle packing theorem—If is a finite planar graph, then a circle packing in the plane whose tangency graph is isomorphic to exists. If is maximal planar, this packing is unique, up to Möbius transformations and reflections in lines.[4]

For every finite planar graph , it is possible to add vertices to to construct a larger planar graph in which is an induced subgraph. Constructing a circle packing from this larger graph, and then removing the circles for the added vertices, produces a circle packing for . This allows the existence of circle packings for arbitrary planar graphs to be derived from the special case for maximal planar graphs.[5]

Existence

Paul Koebe's original proof of the existence of a circle packing for any planar graph is based on his conformal uniformization theorem saying that a finitely connected planar domain is conformally equivalent to a circle domain.[6] A circle domain is a domain, a connected open subset of the plane, whose boundary components are circles or points. It is finitely connected when it has finitely many boundary components, and hence finite first Betti number (the number of generators of its fundamental group). The circle packing is a limiting case of Koebe's result, for domains complementary to the union of disks of the desired circle packing. Koebe conjectured that the finite connectivity assumption was unnecessary in his theorem but was unable to prove it. He & Schramm (1993) extend Koebe's theorem to countably connected domains, and to certain packings of countably many circles.[7]

Thurston's proof is based on the Brouwer fixed point theorem. A former student of Thurston, Oded Schramm, wrote of Thurston's proof that "One can just see the terrible monster swinging its arms in sheer rage, the tentacles causing a frightful hiss, as they rub against each other."[8] Another proof uses a discrete variant of Perron's method of constructing solutions to the Dirichlet problem.[9] Yves Colin de Verdière proved the existence of the circle packing as a minimizer of a convex function on a certain configuration space.[10]

Another proof starts with a circle packing with the correct number of disks but an incorrect pattern of tangencies, for which existence is easy to prove, such as an Apollonian packing. It then corrects the tangencies, one at a time, by removing one edge from the corresponding maximal planar graph and replacing it by the other diagonal of the resulting quadrilateral, at the same time adjusting the packing to match this change, in effect walking in a flip graph of triangulations, until reaching the desired graph of tangencies.[11]

Uniqueness

Thurston observes that this uniqueness is a consequence of the Mostow rigidity theorem. To see this, let be represented by a circle packing. Then the plane in which the circles are packed may be viewed as the boundary of a halfspace model for three-dimensional hyperbolic space; with this view, each circle is the boundary of a plane within the hyperbolic space. One can define a set of disjoint planes in this way from the circles of the packing, and a second set of disjoint planes defined by the circles that circumscribe each triangular gap between three of the circles in the packing. These two sets of planes meet at right angles, and form the generators of a reflection group whose fundamental domain can be viewed as a hyperbolic manifold. By Mostow rigidity, the hyperbolic structure of this domain is uniquely determined, up to isometry of the hyperbolic space; these isometries, when viewed in terms of their actions on the Euclidean plane on the boundary of the half-plane model, translate to Möbius transformations.[12]

Other properties

A result known as the ring lemma controls the sizes of adjacent circles in a Euclidean circle packing. According to the ring lemma, if one circle in a packing is surrounded by a ring of others, then the ratios of the inner circle's radius to the radius of each surrounding circle is at most exponential in . More precisely, this ratio is at most , where denotes the th Fibonacci number.[13]

In the triangle connecting the centers of three mutually tangent circles, the angle formed at the center of one of the circles is monotone decreasing in its radius and monotone increasing in the two other radii.[14] Beardon & Stephenson (1991) described related monotonicity properties of circle packings in the hyperbolic plane that they describe as being a discrete analogue to the Schwarz–Pick theorem in complex differential geometry. They consider any finite circle packing in the hyperbolic plane whose coin graph has the structure of a triangulated disk, and they compare this packing to another packing representing the same graph, obtained by treating the line at infinity of the hyperbolic plane as another circle, tangent to all the circles on the outer boundary of the disk (which become horocycles of infinite radius in the second packing). They prove that in the second packing, each circle's radius is non-decreasing, as is the hyperbolic distance between each pair of centers of tangent circles. If any of the radii or distances is equal, then they all are, and the two packings are congruent.[15]

A Koebe ordering is the sequence of vertices of a planar graph, ordered by their radii in a circle packing (larger to smaller). If there are no ties (which can be achieved by performing a Möbius transformation) then in the resulting ordering each vertex has at most five earlier neighbors, matching the worst-case degeneracy of planar graphs. This property has been generalized as the -admissability of the ordering, the maximum number of disjoint paths of at most steps that all start at the same vertex , continue through vertices later than in the ordering, and end at a vertex earlier than . Any Koebe ordering has -admissability , best possible for planar graphs to within a constant factor.[16]

Applications

The circle packing theorem is a useful tool to study various problems in planar geometry, conformal mappings and planar graphs.

Conformal mapping

A conformal map between two open sets in the plane or in a higher-dimensional space is a continuous function from one set to the other that preserves the angles between any two curves. The Riemann mapping theorem, formulated by Bernhard Riemann in 1851, states that, for any two open topological disks in the plane, there is a conformal map from one disk to the other. Conformal mappings have applications in mesh generation, map projection, and other areas. However, it is not always easy to construct a conformal mapping between two given domains in an explicit way.[17]

A construction of William Thurston uses circle packings to approximate conformal mappings.[18] More precisely, this construction maps an arbitrary open disk to the interior of a circle; the mapping from one topological disk to another disk could then be found by composing the map from to a circle with the inverse of the map from to a circle.[17] Thurston's idea was to pack circles of some small radius in a hexagonal tessellation of the plane, within region , leaving a narrow region near the boundary of , of width , where no more circles of this radius can fit. He then constructs a maximal planar graph from the intersection graph of the circles, together with one additional vertex adjacent to all the circles on the boundary of the packing. By the circle packing theorem, this planar graph can be represented by a circle packing in which all the edges (including the ones incident to the boundary vertex) are represented by tangencies of circles. The circles from the packing of correspond one-for-one with the circles from , except for the boundary circle of which corresponds to the boundary of .[17]

This correspondence of circles can be used to construct a continuous function from to in which each circle and each gap between three circles is mapped from one packing to the other by a Möbius transformation. As goes to infinity, the function determined using Thurston's method from hexagonal packings of radius- circles converges uniformly on compact subsets of to a conformal map from to .[19][17] Practical applications of this method have been hindered by the difficulty of computing circle packings and by its relatively slow convergence rate.[20] However, it has some advantages when applied to non-simply-connected domains and in selecting initial approximations for numerical techniques that compute Schwarz–Christoffel mappings, a different technique for conformal mapping of polygonal domains.[17]

Primal–dual packing, polyhedral realization, and planar separators

A stronger form of the circle packing theorem asserts that any polyhedral graph and its dual graph can be represented by two circle packings, such that the two tangent circles representing a primal graph edge and the two tangent circles representing the dual of the same edge always have their tangencies at right angles to each other at the same point of the plane. This packing is unique up to Möbius transformations and reflections of the plane.[21] As with any circle packing, a primal–dual packing of this type can be lifted from the plane to a sphere by stereographic projection. It can then be used to construct a convex polyhedron that represents the given graph and that has a midsphere, a sphere tangent to all of the edges of the polyhedron. Each vertex of the polyhedron lies outside the sphere, at the apex of a cone tangent to the sphere on the circle corresponding to that vertex. Each face of the polyhedron lies on the plane through its corresponding circle. Each edge of the polyhedron passes from one cone apex to another through the point of tangency of two circles, where both cones are tangent to the sphere. Conversely, if a polyhedron has a midsphere, then the circles formed by the intersections of the sphere with the polyhedron faces and the circles formed by the horizons on the sphere as viewed from each polyhedron vertex form a dual packing of this type.[22]

Möbius transformations of the sphere lead to geometrically different polyhedron realizations. One particular realization, called the canonical polyhedron, is obtained by using a unit sphere and choosing a Möbius transformation that causes the center of the sphere to coincide with the centroid of the points of tangency of the polyhedron edges. All combinatorially equivalent polyhedra will produce in this way the same canonical polyhedron, up to rotations of the sphere.[23] An alternative proof of the planar separator theorem, originally proved in a different way by Lipton and Tarjan,[24] uses a similar idea of applying a Möbius transformation to a spherical circle packing. The construction obtains a circle packing on a sphere, representing the given graph. Next, a Möbius transformation causes the center of the sphere to coincide with a centerpoint of the circle centers, a point in space such that every plane through the centerpoint divides the centers into two subsets that each have size . A uniformly random plane through the center of the sphere intersects of the circles of any packing of circles, in expectation. For the circle packing with the centerpoint at the sphere center, the vertices corresponding to these intersected circles form a separator that, when removed from the graph, leaves connected subgraphs of at most vertices.[25] Circle packing has also been used to explain the success of spectral methods for constructing separators for graphs of bounded genus and bounded degree.[26]

Graph drawing

Circle packing has been used as a frequent tool in graph drawing, the study of methods for visualizing graphs. Fáry's theorem, that every graph that can be drawn without crossings in the plane using curved edges can also be drawn without crossings using straight line segment edges, follows as a simple corollary of the circle packing theorem: by placing vertices at the centers of the circles and drawing straight edges between them, a straight-line planar embedding is obtained.[27]

Malitz & Papakostas (1994) derive a version of the ring lemma and use it to prove that the angular resolution of the drawing in which each vertex is placed at the center of its circle is bounded from below as a function of the maximum degree of the graph: it is at least an inverse-exponential function of this degree.[27] Keszegh, Pach & Pálvölgyi (2013) use a more complicated strategy for placing vertices, near the circle centers on subdivisions of integer lattices, in order to find drawings where the number of distinct edge slopes (the slope number) is at most an exponential function of the degree.[28]

Primal–dual circle packings in the plane can be used to obtain simultaneous orthogonal drawings, straight-line planar drawings of any polyhedral graph and its dual graph, with one dual vertex at infinity, so that each primal and dual pair of edges cross at right angles. Such a drawing can be obtained from a primal–dual circle packing for which one dual circle surrounds the others, with all vertices (except the outer dual vertex) placed at the center of the corresponding circle. The use of circle packings to construct these drawings resolves a problem posed by W. T. Tutte in 1963.[29] A pointed drawing of a given planar graph, in which the edges are drawn as smooth curves that, at each vertex, leave it in the same direction as each other, may be obtained by placing each vertex on the circle of a circle packing (rather than at its center) and drawing each edge as a biarc formed by two circular arcs, perpendicular to the circles of the packing, through the point of tangency of two circles.[30] Circle packings have also been used to obtain strongly monotone drawings of polyhedral graphs. These are straight-line drawings in which each two vertices are connected by a polygonal path that is monotone with respect to the line segment between the two vertices (its orthogonal projection onto this line segment is one-to-one).[31] Another construction involving circle packing produces a Lombardi drawing for any subcubic planar graph, a drawing resembling a two-dimensional soap bubble foam in which the edges are drawn as circular arcs that meet at equal angles at each vertex.[32]

Random walks

Another application of the circle packing theorem is that unbiased limit graphs of bounded-degree planar rooted graphs are almost surely recurrent, meaning that random walks on these graph limits almost surely return to the root infinitely often. The proof involves finding a circle packing that represents the limit graph, and using the ring lemma to bound the sizes of circles a small number of steps from the start of the walk, allowing the walk to be compared to a random walk on an integer grid.[33] Jonnason & Schramm (2000) used circle packings to prove that the expected cover time of a random walk on every -vertex planar graph (the average number of steps of the walk before all vertices are visited) is .[34] A related application involves approximating Brownian motion. For the same sequences of refined circle packings used to approximate conformal mappings of a domain, a random walk on the associated coin graph will reach a boundary vertex with a probability that approaches, in the limit as the circle packings become more fine, the probability that a Brownian motion will reach a nearby point on the boundary of the domain.[2]

Algorithmic aspects

Collins & Stephenson (2003) describe a numerical relaxation algorithm for finding circle packings, based on ideas of William Thurston. The version of the circle packing problem that they solve takes as input a planar graph, in which all the internal faces are triangles and for which the external vertices have been labeled by positive numbers. It produces as output a circle packing whose tangencies represent the given graph, and for which the circles representing the external vertices have the radii specified in the input. As they suggest, the key to the problem is to first calculate the radii of the circles in the packing; once the radii are known, the geometric positions of the circles are not difficult to calculate. They begin with a set of tentative radii that do not correspond to a valid packing, and then repeatedly perform the following steps:

- Choose an internal vertex of the input graph.

- Calculate the total angle that its neighboring circles would cover around the circle for , if the neighbors were placed tangent to each other and to the central circle using their tentative radii.

- Determine a representative radius for the neighboring circles, such that circles of radius would give the same covering angle as the neighbors of give.

- Set the new radius for to be the value for which circles of radius would give a covering angle of exactly .

Each of these steps may be performed with simple trigonometric calculations, and as Collins and Stephenson argue, the system of radii converges rapidly to a unique fixed point for which all covering angles are exactly . Once the system has converged, the circles may be placed one at a time, at each step using the positions and radii of two neighboring circles to determine the center of each successive circle.[35]

Mohar (1993) describes a similar iterative technique for finding simultaneous packings of a polyhedral graph and its dual, in which the dual circles are at right angles to the primal circles. He proves that the method takes time polynomial in the number of circles and in , where is a bound on the distance of the centers and radii of the computed packing from those in an optimal packing.[36]

Generalizations

A version of the circle packing applies to some infinite graphs. In particular, an infinite planar triangulation of an open disk has a locally finite packing in either the Euclidean plane or the hyperbolic plane (but not both). Here, locally finite means that every point of the plane has a neighborhood that intersects only finitely many circles. In the Euclidean case, the packing is unique up to similarity; in the hyperbolic case, it is unique up to isometry.[37]

The circle packing theorem generalizes to graphs that are not planar. If is a graph that can be embedded on a surface (more precisely, an orientable 2-manifold), then there is a Riemannian metric of constant curvature on and a circle packing on whose contact graph is isomorphic to . If is closed (compact and without boundary) and is a triangulation of , then and the packing are unique up to conformal equivalence. If is the sphere, then its geometry is spherical geometry and the equivalence is up to Möbius transformations. If it is a torus, the geometry is locally Euclidean (as a flat torus), and the equivalence is up to scaling by a constant and isometries. If has genus at least 2, then the geometry is locally hyperbolic and the equivalence is up to isometries.

Another generalization of the circle packing theorem involves replacing the condition of tangency with a specified intersection angle between circles corresponding to neighboring vertices. One version is as follows. Suppose that is a finite 3-connected planar graph (that is, a polyhedral graph), then there is a pair of circle packings, one whose intersection graph is isomorphic to , another whose intersection graph is isomorphic to the planar dual of , and for every vertex in and face adjacent to it, the circle in the first packing corresponding to the vertex intersects orthogonally with the circle in the second packing corresponding to the face.[1] For instance, applying this result to the graph of the tetrahedron gives, for any four mutually tangent circles, a second set of four mutually tangent circles each of which is orthogonal to three of the first four.[38] A further generalization, replacing intersection angle with inversive distance, allows the specification of packings in which some circles are required to be disjoint from each other rather than crossing or being tangent.[39]

Yet another variety of generalizations allow shapes that are not circles.[3] Suppose that is a finite planar graph, and to each vertex of corresponds a shape , which is homeomorphic to the closed unit disk and whose boundary is smooth. Then there is a packing in the plane such that if and only if and for each the set is obtained from by translating and scaling. (In the original circle packing theorem, there are three real parameters per vertex, two of which describe the center of the corresponding circle and one of which describe the radius, and there is one equation per edge. This also holds in this generalization.) This result, from Oded Schramm's 1990 Ph.D. thesis,[40] has become known as Schramm's "monster packing theorem".[41] One proof of this generalization can be obtained by applying Koebe's original proof[42] and the theorem of Brandt[43] and Harrington[44] stating that any finitely connected domain is conformally equivalent to a planar domain whose boundary components have specified shapes, up to translations and scaling.[40]

History

Ken Stephenson writes that "there is indeed a long tradition behind our story", and attributes the familiar hexagonal packing of congruent circles to folklore.[45] Other early works on circle packings with specific patterns of tangency include:

- Descartes' theorem on the radii of four mutually tangent circles, stated by René Descartes in 1643[46] and by Japanese mathematician Yamaji Nushizumi in 1751,[47]

- a 1706 letter by Leibniz mentioning a variant of the Apollonian gasket, an infinite fractal circle packing formed by repeatedly placing a circle within each circular triangle between larger circles in the packing,[48] and

- the 1910 work of Arnold Emch on Doyle spirals in phyllotaxis (the mathematics of plant growth).[49]

The circle packing theorem itself was first stated and proved by Paul Koebe in 1936.[42] In the 1970s, William Thurston rediscovered the circle packing theorem,[45] and noted that it followed from the work of E. M. Andreev.[50] He mentioned these results in a 1978 talk at the International Congress of Mathematicians; in the same year, German mathematician Gerd Wegner also conjectured that the circle packing theorem holds.[51] At the Bieberbach conference in 1985, Thurston proposed a scheme for using the circle packing theorem to obtain a homeomorphism of a simply connected proper subset of the plane onto the interior of the unit disk, and he conjectured that this scheme converges to the Riemann mapping as the radii of the circles tend to zero.[18] Thurston's conjecture was proven in 1987 by Burton Rodin and Dennis Sullivan.[19] Thurston's work in this area brought the topic of circle packings to the attention of mathematicians and led to the formation of a research community centered on this idea.[45]

See also

- Circle packing, arrangements of circles studied with respect to packing density rather than tangency

- Ford circles, a packing of circles along the rational number line

- Penny graph, the coin graphs whose circles all have equal radii

Notes

- ^ a b Brightwell & Scheinerman (1993).

- ^ a b Dubejko (1997).

- ^ a b de Fraysseix, Ossona de Mendez & Rosenstiehl (1994).

- ^ a b Thurston (2002), p. 330, Corollary 13.6.2.

- ^ A version of this construction for 2-vertex-connected planar graphs is given by Thurston (2002, p. 331). Thurston adds one vertex per face, incident to all vertices in the face; this may fail when a vertex occurs more than once around the face boundary, as may happen in plane graphs that are not 2-vertex-connected. de Fraysseix, Ossona de Mendez & Rosenstiehl (1994, p. 241, Theorem 3.2) claim that two added vertices per face suffice, but do not provide details. A more complicated augmentation strategy that does not require 2-connectivity, adding a binary tree within each face and then triangulating the new faces created by this tree, is given by Alam et al. (2014).

- ^ Koebe (1936).

- ^ He & Schramm (1993).

- ^ Rohde (2011), p. 1628.

- ^ Beardon & Stephenson (1991); Carter & Rodin (1992).

- ^ Colin de Verdière (1991).

- ^ Connelly & Gortler (2021).

- ^ Thurston (2002), pp. 331–332.

- ^ Rodin & Sullivan (1987, p. 352); Hansen (1988); Aharonov (1997)

- ^ Stephenson (2005), pp. 63–64, Lemma 6.2 (Monotonicity in Triangles).

- ^ Beardon & Stephenson (1991).

- ^ Nederlof, Pilipczuk & Węgrzycki (2023).

- ^ a b c d e Stephenson (1999).

- ^ a b Thurston (1985).

- ^ a b Rodin & Sullivan (1987).

- ^ Stephenson (1999): "Circle packing certainly cannot compete with the classical numerical methods for speed and accuracy."

- ^ Schramm (1992); Brightwell & Scheinerman (1993); Sachs (1994)

- ^ Schramm (1992); Sachs (1994). Schramm states that the existence of an equivalent polyhedron with a midsphere was claimed by Koebe (1936), but that Koebe only proved this result for polyhedra with triangular faces. Schramm credits the full result to William Thurston, but the relevant portion of Thurston's lecture notes (Thurston 2002, pp. 331–332) again only states the result explicitly for triangulated polyhedra.

- ^ Ziegler (1995).

- ^ Lipton & Tarjan (1979).

- ^ Miller et al. (1997).

- ^ Kelner (2006).

- ^ a b Malitz & Papakostas (1994).

- ^ Keszegh, Pach & Pálvölgyi (2013).

- ^ Tutte (1963); Brightwell & Scheinerman (1993); Felsner & Rote (2019)

- ^ Aichholzer et al. (2012).

- ^ Felsner et al. (2016).

- ^ Eppstein (2014).

- ^ Benjamini & Schramm (2001).

- ^ Jonnason & Schramm (2000).

- ^ Collins & Stephenson (2003).

- ^ Mohar (1993).

- ^ He & Schramm (1995).

- ^ Coxeter (2006).

- ^ Bowers & Stephenson (2004).

- ^ a b Schramm (1990).

- ^ Rohde (2011).

- ^ a b Koebe (1936).

- ^ Brandt (1980).

- ^ Harrington (1982).

- ^ a b c Stephenson (2003).

- ^ Bos (2010).

- ^ Michiwaki (2008).

- ^ Leibniz (1706).

- ^ Emch (1910).

- ^ Andreev (1970a, 1970b)

- ^ Sachs (1994).

References

- Aharonov, Dov (1997), "The sharp constant in the ring lemma", Complex Variables, 33 (1–4): 27–31, doi:10.1080/17476939708815009, MR 1624890

- Aichholzer, Oswin; Rote, Günter; Schulz, André; Vogtenhuber, Birgit (2012), "Pointed drawings of planar graphs", Computational Geometry, 45 (9): 482–494, doi:10.1016/j.comgeo.2010.08.001, MR 2926292

- Alam, Md. Jawaherul; Eppstein, David; Goodrich, Michael T.; Kobourov, Stephen G.; Pupyrev, Sergey (2014), "Balanced circle packings for planar graphs", in Duncan, Christian A.; Symvonis, Antonios (eds.), Graph Drawing - 22nd International Symposium, GD 2014, Würzburg, Germany, September 24-26, 2014, Revised Selected Papers, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol. 8871, Springer, pp. 125–136, arXiv:1408.4902, doi:10.1007/978-3-662-45803-7_11

- Andreev, E. M. (1970a), "Convex polyhedra in Lobačevskiĭ spaces", Matematicheskii Sbornik, New Series, 81 (123): 445–478, doi:10.1070/SM1970v010n03ABEH001677, MR 0259734

- Andreev, E. M. (1970b), "Convex polyhedra of finite volume in Lobačevskiĭ space", Matematicheskii Sbornik, New Series, 83 (125): 256–260, doi:10.1070/SM1970v012n02ABEH000920, MR 0273510

- Beardon, Alan F.; Stephenson, Kenneth (1991), "The Schwarz-Pick lemma for circle packings", Illinois J. Math., 35 (4): 577–606, doi:10.1215/ijm/1255987673

- Benjamini, Itai; Schramm, Oded (2001), "Recurrence of distributional limits of finite planar graphs", Electronic Journal of Probability, 6, doi:10.1214/EJP.v6-96, MR 1873300

- Bos, Erik-Jan (2010), "Princess Elizabeth of Bohemia and Descartes' letters (1650–1665)", Historia Mathematica, 37 (3): 485–502, doi:10.1016/j.hm.2009.11.004

- Bowers, Philip L.; Stephenson, Kenneth (2004), "8.2 Inversive distance packings", Uniformizing dessins and Belyĭ maps via circle packing, Memoirs of the American Mathematical Society, vol. 170, pp. 78–82, doi:10.1090/memo/0805, MR 2053391

- Brandt, M. (1980), "Ein Abbildungssatz fur endlich-vielfach zusammenhangende Gebiete", Bull. De la Soc. Des Sc. Et des Lettr. De Łódź, 30

- Brightwell, Graham R.; Scheinerman, Edward R. (1993), "Representations of planar graphs", SIAM Journal on Discrete Mathematics, 6 (2): 214–229, doi:10.1137/0406017

- Carter, Ithiel; Rodin, Burt (1992), "An inverse problem for circle packing and conformal mapping", Transactions of the American Mathematical Society, 334 (2): 861–875, doi:10.1090/S0002-9947-1992-1081937-X

- Colin de Verdière, Yves (1991), "Une principe variationnel pour les empilements de cercles", Inventiones Mathematicae, 104 (1): 655–669, doi:10.1007/BF01245096

- Collins, Charles R.; Stephenson, Kenneth (2003), "A circle packing algorithm", Computational Geometry. Theory and Applications, 25 (3): 233–256, doi:10.1016/S0925-7721(02)00099-8, MR 1975216

- Connelly, Robert; Gortler, Steven J. (2021), "Packing disks by flipping and flowing", Discrete & Computational Geometry, 66 (4): 1262–1285, arXiv:1910.02327, doi:10.1007/s00454-020-00242-8, MR 4333292

- Coxeter, H. S. M. (2006), "An absolute property of four mutually tangent circles", Non-Euclidean geometries, Math. Appl. (N. Y.), vol. 581, New York: Springer, pp. 109–114, doi:10.1007/0-387-29555-0_5, ISBN 978-0-387-29554-1, MR 2191243

- de Fraysseix, Hubert; Ossona de Mendez, Patrice; Rosenstiehl, Pierre (1994), "On triangle contact graphs", Combinatorics, Probability and Computing, 3 (2): 233–246, doi:10.1017/S0963548300001139, MR 1288442

- Dubejko, Tomasz (1997), "Circle-packing connections with random walks and a finite volume method", Séminaire de Théorie Spectrale et Géométrie, No. 15, Année 1996–1997, vol. 15, Univ. Grenoble I, Saint-Martin-d'Hères, pp. 153–161, doi:10.5802/tsg.187, MR 1604271

- Emch, Arnold (1910), "Sur quelques exemples mathématiques dans les sciences naturelles", L'Enseignement mathématique (in French), 12: 114–123

- Eppstein, David (2014), "A Möbius-invariant power diagram and its applications to soap bubbles and planar Lombardi drawing", Discrete & Computational Geometry, 52 (3): 515–550, doi:10.1007/s00454-014-9627-0, MR 3257673

- Felsner, Stefan; Igamberdiev, Alexander; Kindermann, Philipp; Klemz, Boris; Mchedlidze, Tamara; Scheucher, Manfred (2016), "Strongly Monotone Drawings of Planar Graphs", in Fekete, Sándor P.; Lubiw, Anna (eds.), 32nd International Symposium on Computational Geometry, SoCG 2016, Boston, MA, USA, June 14–18, 2016, LIPIcs, vol. 51, Schloss Dagstuhl - Leibniz-Zentrum für Informatik, pp. 37:1–37:15, doi:10.4230/LIPICS.SOCG.2016.37

- Felsner, Stefan; Rote, Günter (2019), "On primal–dual circle representations", in Fineman, Jeremy T.; Mitzenmacher, Michael (eds.), 2nd Symposium on Simplicity in Algorithms, SOSA 2019, San Diego, CA, USA, January 8–9, 2019, OASIcs, vol. 69, Schloss Dagstuhl - Leibniz-Zentrum für Informatik, pp. 8:1–8:18, doi:10.4230/OASICS.SOSA.2019.8

- Hansen, Lowell J. (1988), "On the Rodin and Sullivan ring lemma", Complex Variables, 10 (1): 23–30, doi:10.1080/17476938808814284, MR 0946096

- Harrington, Andrew N. (1982), "Conformal mappings onto domains with arbitrarily specified boundary shapes", Journal d'Analyse Mathématique, 41 (1): 39–53, doi:10.1007/BF02803393

- He, Zheng-Xu; Schramm, Oded (1993), "Fixed points, Koebe uniformization and circle packings", Annals of Mathematics, Second Series, 137 (2): 369–406, doi:10.2307/2946541, JSTOR 2946541, MR 1207210

- He, Zheng-Xu; Schramm, O. (1995), "Hyperbolic and parabolic packings", Discrete & Computational Geometry, 14 (2): 123–149, doi:10.1007/BF02570699, MR 1331923

- Jonnason, Johan; Schramm, Oded (2000), "On the cover time of planar graphs", Electronic Communications in Probability, 5: 85–90, doi:10.1214/ECP.v5-1022

- Kelner, Jonathan A. (2006), "Spectral partitioning, eigenvalue bounds, and circle packings for graphs of bounded genus", SIAM Journal on Computing, 35 (4): 882–902, doi:10.1137/S0097539705447244, MR 2203731; also published as a 2005 MIT master's thesis, hdl:1721.1/30169

- Keszegh, Balázs; Pach, János; Pálvölgyi, Dömötör (2013), "Drawing planar graphs of bounded degree with few slopes", SIAM Journal on Discrete Mathematics, 27 (2): 1171–1183, doi:10.1137/100815001, MR 3071400

- Koebe, Paul (1936), "Kontaktprobleme der konformen Abbildung", Ber. Sächs. Akad. Wiss. Leipzig, Math.-Phys. Kl., 88: 141–164

- Leibniz, Gottfried Wilhelm (March 11–17, 1706), Letter to des Bosses, translated by Ottaviani, Osvaldo – via Technion

- Lipton, Richard J.; Tarjan, Robert E. (1979), "A separator theorem for planar graphs", SIAM Journal on Applied Mathematics, 36 (2): 177–189, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.104.6528, doi:10.1137/0136016

- Malitz, Seth; Papakostas, Achilleas (1994), "On the angular resolution of planar graphs", SIAM Journal on Discrete Mathematics, 7 (2): 172–183, doi:10.1137/S0895480193242931, MR 1271989

- Michiwaki, Yoshimasa (2008), "Geometry in Japanese mathematics", in Selin, Helaine (ed.), Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Western Cultures, Springer Netherlands, pp. 1018–1019, doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-4425-0_9133, ISBN 978-1-4020-4559-2

- Miller, Gary L.; Teng, Shang-Hua; Thurston, William; Vavasis, Stephen A. (1997), "Separators for sphere-packings and nearest neighbor graphs", Journal of the ACM, 44 (1): 1–29, doi:10.1145/256292.256294

- Mohar, Bojan (1993), "A polynomial time circle packing algorithm", Discrete Mathematics, 117 (1–3): 257–263, doi:10.1016/0012-365X(93)90340-Y

- Nederlof, Jesper; Pilipczuk, Michał; Węgrzycki, Karol (2023), "Bounding generalized coloring numbers of planar graphs using coin models", Electronic Journal of Combinatorics, 30 (3) 3.33, arXiv:2201.09340, doi:10.37236/11095, MR 4644253

- Rodin, Burton; Sullivan, Dennis (1987), "The convergence of circle packings to the Riemann mapping", Journal of Differential Geometry, 26 (2): 349–360, doi:10.4310/jdg/1214441375

- Rohde, Steffen (2011), "Oded Schramm: from circle packing to SLE", Annals of Probability, 39 (5): 1621–1667, arXiv:1007.2007, doi:10.1214/10-AOP590; also printed in Selected Works of Oded Schramm, Springer, 2011, doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-9675-6_1

- Sachs, Horst (1994), "Coin graphs, polyhedra, and conformal mapping", Discrete Mathematics, 134 (1–3): 133–138, doi:10.1016/0012-365X(93)E0068-F, MR 1303402, Zbl 0808.05043

- Schramm, Oded (1990), Packing Two-Dimensional Bodies With Prescribed Combinatorics And Applications To The Construction of Conformal and Quasi-Conformal Mappings (Ph.D. thesis), Princeton University, ProQuest 303827410; modified and reprinted as "Combinatorically Prescribed Packings and Applications to Conformal and Quasiconformal Maps", arXiv:0709.0710, 2007

- Schramm, Oded (1992), "How to cage an egg", Inventiones Mathematicae, 107 (3): 543–560, doi:10.1007/BF01231901, MR 1150601, Zbl 0726.52003

- Stephenson, Kenneth (1999), "The approximation of conformal structures via circle packing" (PDF), Computational methods and function theory 1997 (Nicosia), Ser. Approx. Decompos., vol. 11, World Scientific, pp. 551–582, MR 1700374

- Stephenson, Ken (2003), "Circle packing: a mathematical tale" (PDF), Notices of the American Mathematical Society, 50: 1376–1388

- Stephenson, Ken (2005), Introduction to circle packing, the theory of discrete analytic functions, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

- Thurston, William (1985), The finite Riemann mapping theorem, Invited talk at the International Symposium at Purdue University on the occasion of the proof of the Bieberbach conjecture

- Thurston, William (March 2002), "§13.6, Andreev's theorem and generalizations, and §13.7, Constructing patterns of circles", The Geometry and Topology of 3-manifolds, MSRI Publications, pp. 330–346, Electronic version 1.1, retrieved 2025-12-09

- Tutte, W. T. (1963), "How to draw a graph", Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society, Third Series, 13: 743–767, doi:10.1112/plms/s3-13.1.743, MR 0158387

- Ziegler, Günter M. (1995), Lectures on Polytopes, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, vol. 152, Springer-Verlag, pp. 117–118, arXiv:math/9909177, doi:10.1007/978-1-4613-8431-1, ISBN 0-387-94365-X, MR 1311028, Zbl 0823.52002

Further reading

- Beardon, Alan F.; Stephenson, Kenneth (1990), "The uniformization theorem for circle packings", Indiana Univ. Math. J., 39 (4): 1383–1425, doi:10.1512/iumj.1990.39.39062

- Connelly, Robert; Zhang, Zhen (2025), "Rigidity of circle packings with flexible radii", Discrete & Computational Geometry, 74 (3): 585–618, arXiv:2206.07165, doi:10.1007/s00454-025-00776-9, MR 4965850

External links

- CirclePack (free software for constructing circle packings from graphs, by Kenneth Stephenson, Univ. of Tennessee)