Coombs' method

In the following article we will analyze in detail the importance of Coombs' method in the current context. Coombs' method has become a topic of great relevance in modern society, generating debates, conflicting opinions and endless repercussions in different areas. Throughout history, Coombs' method has proven to be a determining factor in the evolution of humanity, influencing cultural, social, political and economic aspects. In this sense, it is crucial to understand the importance of Coombs' method and its impact on the contemporary world. Through a critical and analytical approach, we will explore the various dimensions of Coombs' method and its relevance in the current context, with the aim of providing a comprehensive vision on this topic of general interest.

| A joint Politics and Economics series |

| Social choice and electoral systems |

|---|

|

|

|

Coombs' method is a ranked voting system. Like instant-runoff (IRV-RCV), Coombs' method is a sequential-loser method, where the last-place finisher according to one method is eliminated in each round. However, unlike in instant-runoff, each round has electors voting against their least-favorite candidate; the candidate ranked last by the most voters is eliminated.[1]

The method fails several voting system criteria, including Condorcet's majority criterion, monotonicity, participation, and clone-independence.[2][3] However, it does satisfy Black's single-peaked median voter criterion.[1]: prop. 2

History

The method was popularized by Clyde Coombs.[1] It was described by Edward J. Nanson as the "Venetian method"[4] (which should not be confused with the Republic of Venice's use of score voting in elections for Doge).

Procedures

Each voter rank-orders all of the candidates on their ballot. If a candidate is ranked first by a majority of voters, that candidate wins. Otherwise, the candidate ranked last by the largest number (plurality) of voters is eliminated, making each individual round equivalent to anti-plurality voting. Conversely, under instant-runoff voting, the candidate ranked first (among non-eliminated candidates) by the fewest voters is eliminated.

In some sources, the elimination proceeds regardless of whether any candidate is ranked first by a majority of voters, and the last candidate to be eliminated is the winner.[5] This variant of the method can result in a different winner than the former one (unlike in instant-runoff voting, where checking to see if any candidate is ranked first by a majority of voters is only a shortcut that does not affect the outcome).

An example

| 42% of voters |

26% of voters |

15% of voters |

17% of voters |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

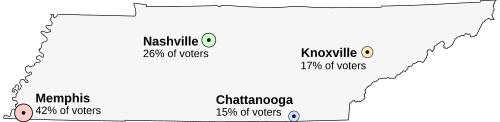

Suppose Tennessee is holding an election on the location of its capital. The population is split between four cities, and all the voters want the capital to be as close to them as possible. The options are:

- Memphis, large but far to the west

- Nashville, medium, near the center

- Chattanooga, small and in the east

- Knoxville, small and isolated

Assuming all of the voters vote sincerely (strategic voting is discussed below), the results would be as follows, by percentage:

| City | Round 1 | Round 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First | Last | First | Last | |

| Memphis | 42 | 58 | ||

| Nashville | 26 | 0 | ||

| Chattanooga | 15 | 0 | 15 | |

| Knoxville | 17 | 42 | 17 | |

- In the first round, no candidate has an absolute majority of first-place votes (51).

- Memphis, having the most last-place votes (26+15+17=58), is therefore eliminated.

- In the second round, Memphis is out of the running, and so must be factored out. Memphis was ranked first on Group A's ballots, so the second choice of Group A, Nashville, gets an additional 42 first-place votes, giving it an absolute majority of first-place votes (68 versus 15+17=32), and making it the winner.

- Note that the last-place votes are only used to eliminate a candidate in a voting round where no candidate achieves an absolute majority; they are disregarded in a round where any candidate has more than 50%. Thus last-place votes play no role in the final round.

In practice

The voting rounds used in the reality television program Survivor could be considered a variation of Coombs' method but with sequential voting rounds. Everyone votes for one candidate they support for elimination each round, and the candidate with a plurality of that vote is eliminated. A strategy difference is that sequential rounds of voting means the elimination choice is fixed in a ranked ballot Coombs' method until that candidate is eliminated.

Potential for strategic voting

Like anti-plurality voting, Coombs' rule is extremely vulnerable to strategic voting. As a result, it is more often used as an example of a pathological voting rule than a serious proposal.[6] The equilibrium position for Coombs' method is extremely sensitive to incomplete ballots and strategic nomination because the vast majority of voters' effects on the election come from how they fill out the bottom of their ballots.[6] As a result, voters have a strong incentive to rate the strongest candidates last to defeat them in earlier rounds.[7]

See also

Notes

- ^ a b c Grofman, Bernard; Feld, Scott L. (2004-12-01). "If you like the alternative vote (a.k.a. the instant runoff), then you ought to know about the Coombs rule". Electoral Studies. 23 (4): 641–659. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2003.08.001. ISSN 0261-3794.

- ^ Nurmi, Hannu (1983-04-01). "Voting Procedures: A Summary Analysis". British Journal of Political Science. 13 (2). Cambridge University Press: 181–208. doi:10.1017/S0007123400003215. Retrieved 2024-05-19.

- ^ Nurmi, Hannu (2012-12-06). Comparing Voting systems. Theory and Decision Library A. Vol. 3 (Illustrated ed.). Springer Dordrecht. p. 209. doi:10.1007/978-94-009-3985-1. ISBN 9789400939851.

- ^ Royal Society of Victoria (Melbourne, Vic ) (1864). Transactions and proceedings of the Royal Society of Victoria . American Museum of Natural History Library. Melbourne : The Society.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: publisher location (link) - ^ Pacuit, Eric, "Voting Methods", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2017 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.)

- ^ a b "Data on Manipulability"

- ^ Smith, Warren D. (12 July 2006). "Descriptions of single-winner voting systems" (PDF). Voting Systems.