Spanish Peaks

On this occasion, we will enter the exciting world of Spanish Peaks. This topic has captivated the attention of countless people over time, its importance and relevance are indisputable. Spanish Peaks is a topic that covers a wide range of aspects and can be approached from different perspectives. In this article, we will thoroughly explore the different aspects of Spanish Peaks, from its origins to its impact today. We are sure that this detailed analysis will be of great interest to our readers, since Spanish Peaks is a topic that has left its mark on history and continues to arouse lively interest today.

| Spanish Peaks | |

|---|---|

| Huajatolla | |

| |

| Highest point | |

| Peak | West Spanish Peak |

| Elevation | 13,631 ft (4,155 m) NAVD 88 |

| Prominence | 3,666 ft (1,117 m) |

| Coordinates | 37°22′32″N 104°59′36″W / 37.375588°N 104.993396°W |

| Dimensions | |

| Area | 28 sq mi (73 km2) |

| Geography | |

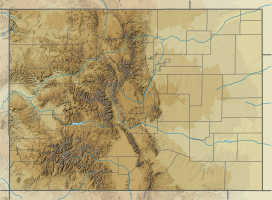

Map of Colorado | |

| Location | Huerfano County, Colorado |

| Range coordinates | 37°23′N 104°57′W / 37.38°N 104.95°W |

| Designated | 1976 |

The Spanish Peaks are a pair of prominent mountains located in southwestern Huerfano County, Colorado. The Comanche people call them Huajatolla (/wɑːhɑːˈtɔɪə/ wah-hah-TOY-ə) or Wa-ha-toy-yah meaning "double mountain" or "Breasts of the Earth".

The two peaks, East Spanish Peak at elevation 12,688 feet (3,867 m) and West Spanish Peak at elevation 13,631 feet (4,155 m), are east of, and separate from, the Culebra Range of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains. Both of the Spanish Peaks are higher than any point in the United States farther east. The Spanish Peaks are situated 100 miles (160 km) due south of Colorado Springs.

The Spanish Peaks were formed by two separate shallow (or hypabyssal) igneous intrusions during the Late-Oligocene epoch of the Paleogene Period. West Spanish Peak is an older (24.59 +/- 0.13 Ma) quartz syenite. East Spanish Peak (23.36 +/- 0.18 Ma) is composed of a granodiorite porphyry surrounded by a more aerially-extensive exposure of granite porphyry. The granite porphyry represents the evolved upper portion of the magma chamber while the interior granodiorite porphyry is exposed by erosion at the summit.

The Spanish Peaks were designated a National Natural Landmark in 1976 as two of the best known examples of igneous dikes.

They were an important landmark on the Santa Fe Trail, the first sighting of the Rocky Mountains for travelers on the trail. The mountains can be seen as far north as Colorado Springs (102 miles ), points south to Raton, New Mexico (65 miles ), and points on the Great Plains east of Trinidad (up to 100 miles ). A classic book about travel to the region in the 1840s is Wah-to-yah and the Taos Trail, by Lewis Garrard.

The Spanish Peaks Wilderness area of 17,855 acres (28 sq mi; 72 km2) encompasses the summits of both Spanish peaks. Hiking is popular in the wilderness area.

See also

References

- ^ a b c "Spanish Peaks". Peakbagger.com.

- ^ Christofferson, Nancy (June 25, 2015). "The Spanish Peaks: Legends". Huerfano World Journal. Retrieved August 19, 2020.

- ^ Chronic, Halka (1998). Roadside Geology of Colorado. Mountain Press Publishing Company. p. 36. ISBN 0-87842-105-X.

- ^ "Igneous Petrology of the Spanish Peaks". February 2012.

- ^ Penn, B. S. (1994). An Investigation of the temporal and geochemical characteristics and petrogenetic origins of the Spanish Peaks intrusive rocks of south-central Colorado (Thesis). Colorado School of Mines. p. 199.

- ^ Penn, B.S.; Lindsey, D.A. (2009). "40Ar/39Ar dates for the Spanish Peaks intrusions of south-central Colorado". Rocky Mountain Geology. 44 (1): 17–32. doi:10.2113/gsrocky.44.1.17.

- ^ "National Registry of Natural Landmarks" (PDF). National Park Service. June 2009.

External links

Media related to Spanish Peaks at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Spanish Peaks at Wikimedia Commons- National Park Service